Learn beautiful Animations in powerpoint – https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLqx6PmnTc2qjX0JdZb1VTemUgelA4QPB3

Table of Contents

ToggleLearn Excel Skills – https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLqx6PmnTc2qhlSadfnpS65ZUqV8nueAHU

Learn Microsoft Word Skills – https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLqx6PmnTc2qib1EkGMqFtVs5aV_gayTHN

1. Introduction

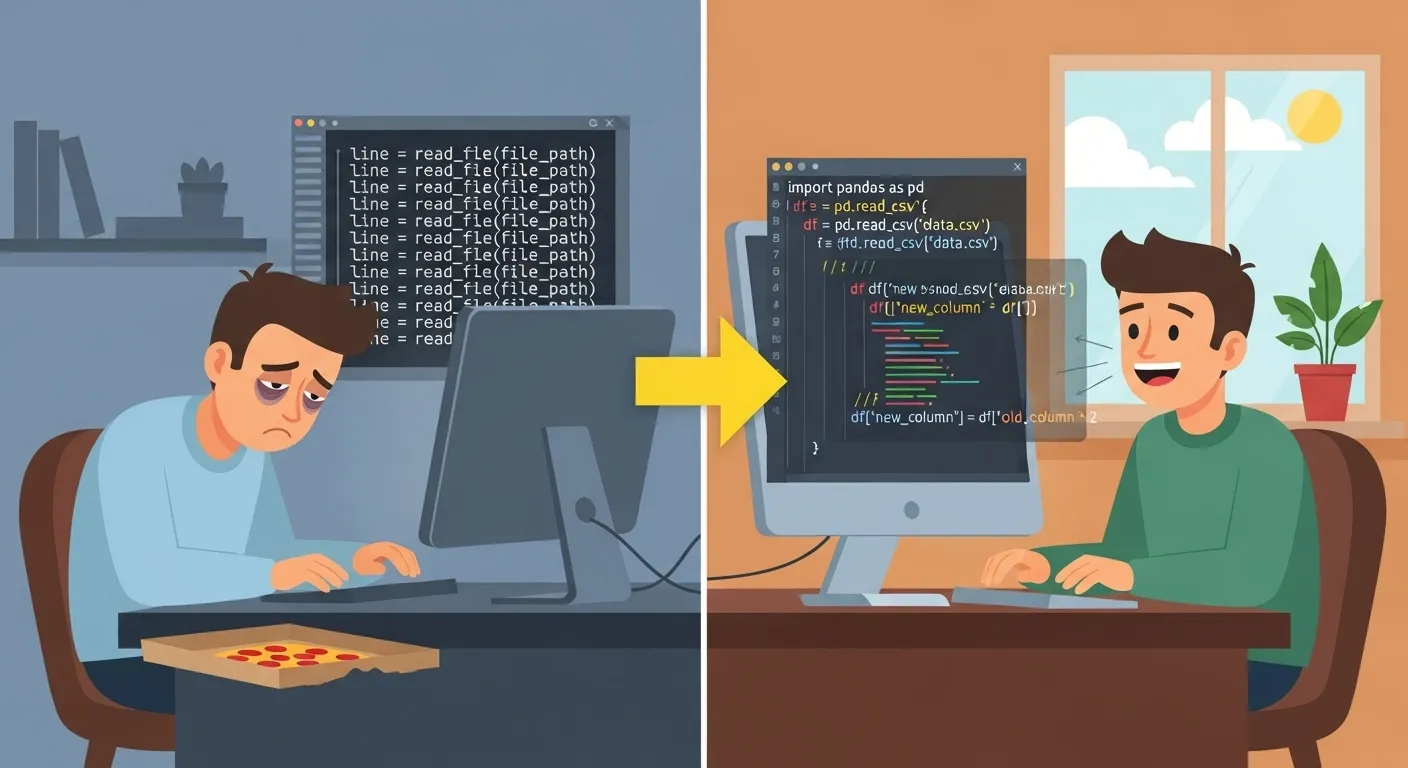

Let’s be honest: every programmer at some point has daydreamed about code that magically writes more code. Why? Because that’s the closest we get to feeling like wizards with keyboards instead of wands. And in the world of Python, this isn’t just fantasy—it’s called metaprogramming.

Metaprogramming is often described as the pinnacle of programming because it lets you bend the rules of the language itself. Instead of just telling Python what to do, you can teach Python how to teach itself what to do. (Yes, very Inception-like.)

So, what exactly is Python metaprogramming? Simply put, it’s the art of writing code that writes code. This means your programs don’t just execute instructions—they can dynamically create, modify, or extend themselves at runtime. Sounds a little dangerous, a little sci-fi, and a lot of fun.

But why should you care? Because in modern applications—from Django’s ORM magic to automated ML pipelines—metaprogramming powers some of the most elegant shortcuts in Python development. It allows frameworks to feel “smart,” automations to feel seamless, and developers (like you) to avoid endless boilerplate.

In this article, we’ll dive deep into:

-

What metaprogramming is and why it matters.

-

Core tools like introspection, dynamic code execution, decorators, and metaclasses.

-

Real-world use cases that make your favorite frameworks tick.

-

Best practices (and cautionary tales) when using these Python advanced features.

By the end, you’ll not only understand metaprogramming—you’ll probably be itching to experiment with writing your own code-generating code. Just remember: with great power comes great debugging sessions.

2. The Concept of Metaprogramming

2.1 What is Metaprogramming?

At its core, metaprogramming is programming about programming. Regular programming is like writing a recipe: “Take flour, add eggs, stir, bake.” Metaprogramming is like writing a recipe that creates new recipes on the fly.

Instead of just telling the computer what to do, you’re teaching it how to create instructions for itself. That’s the difference:

-

Regular programming: static instructions.

-

Metaprogramming: flexible instructions that adapt, modify, or generate new instructions at runtime.

2.2 Types of Metaprogramming Approaches

There are a few flavors of metaprogramming across languages:

-

Compile-time vs Runtime

-

In languages like C++ or Rust, metaprogramming often happens at compile-time (templates, macros).

-

In Python, since it’s interpreted, most magic happens at runtime.

-

-

Declarative vs Imperative

-

Declarative: you describe what you want, and the system figures out the details (think SQLAlchemy models).

-

Imperative: you explicitly write the logic to generate or modify code.

-

Python shines because it leans heavily into runtime + declarative styles, making it approachable yet powerful.

2.3 Why Python is a Great Language for Metaprogramming

Why do people rave about Python metaprogramming? Three big reasons:

-

Dynamic Typing: Python doesn’t lock types at compile time, so you can modify classes, attributes, or functions on the fly.

-

Reflection & Introspection: You can peek inside objects—ask them what attributes they have, what type they are, or even rewrite them.

-

First-Class Functions & Objects: In Python, functions and classes are just objects, which means you can pass them around, wrap them, or generate them dynamically.

Put together, these features make Python one of the friendliest languages for exploring code that writes code.

3. Python Introspection: The Building Block of Metaprogramming

3.1 What is Introspection?

Introspection is Python’s way of saying: “Let’s look under the hood while the engine is still running.” It allows you to examine objects at runtime and discover their attributes, methods, or even parent classes.

For example:

x = [1, 2, 3]

print(type(x)) # <class 'list'>

print(dir(x)) # Shows all methods/attributes of a list

print(callable(x)) # False, lists aren’t callable

This ability to inspect and adapt on the fly is what powers advanced tricks like ORMs, testing frameworks, and even debuggers.

3.2 Useful Built-in Functions for Introspection

Here are some Python tools in your introspection toolkit:

-

type(obj)→ Tells you the type. -

id(obj)→ Gives the memory address (handy for object tracking). -

dir(obj)→ Lists all attributes & methods. -

callable(obj)→ Checks if you can “call” it like a function. -

isinstance(obj, cls)→ Confirms ifobjis an instance ofcls. -

issubclass(sub, parent)→ Confirms ifsubis derived fromparent.

Example:

class Animal: pass

class Dog(Animal): passprint(isinstance(d, Dog)) # True

print(issubclass(Dog, Animal)) # True

3.3 Use Cases of Introspection

-

Debugging: Ever used

dir()in a Python REPL when you couldn’t remember a method? That’s introspection. -

Dynamic Class Modification: Frameworks like Django inspect models to auto-generate database tables.

-

Automated Testing: Test frameworks like

unittestauto-discover tests by introspecting function names.

Without introspection, Python would feel far less dynamic—and metaprogramming would be nearly impossible.

3. Python Introspection: The Building Block of Metaprogramming

If metaprogramming is the superpower, then introspection is the cape. Without it, Python couldn’t pull off half the dynamic tricks that make it so loveable (and sometimes confusing). Introspection basically means: “Hey Python object, tell me who you are and what you can do—while you’re running.”

This makes it possible to write flexible programs that adapt in real time. Debuggers, frameworks, and even IDE autocomplete features rely on introspection to do their magic.

3.1 What is Introspection?

Introspection in Python is the ability to examine objects at runtime. Instead of digging through documentation or guessing, you can just ask an object directly about its type, methods, and attributes.

Example:

x = [42, 7, 99]

print(type(x)) # <class ‘list’>

print(dir(x)) # [‘__add__’, ‘__class__’, …, ‘append’, ‘pop’, ‘sort’]

print(callable(x)) # False, because lists aren’t callable

Think of it as Python’s equivalent of checking someone’s résumé mid-interview:

-

type()→ “What’s your job title?” -

dir()→ “What skills do you have?” -

callable()→ “Can you actually do something if I call your name?”

This runtime peek is what separates Python from more rigidly-typed languages like Java or C++.

3.2 Useful Built-in Functions for Introspection

Here’s your introspection toolbox:

-

type(obj)→ Get the type of an object. -

id(obj)→ Memory address (unique identifier during runtime). -

dir(obj)→ List all attributes and methods available. -

callable(obj)→ Check if object can be “called” like a function. -

isinstance(obj, cls)→ Check if object belongs to a class. -

issubclass(sub, parent)→ Check inheritance relationships.

Example:

class Animal:

passdef bark(self):

return “Woof!”

print(isinstance(d, Animal)) # True

print(issubclass(Dog, Animal)) # True

print(dir(Dog)) # Shows bark(), __init__, etc.

Python lets you poke and prod any object like a curious toddler pulling apart a Lego spaceship.

3.3 Use Cases of Introspection

So why should you care about introspection beyond party tricks?

-

Debugging

Ever typeddir(obj)in a Python shell when you couldn’t remember the exact method name? That’s introspection in action. Debuggers and IDEs rely heavily on this to show you available methods or autocompletion hints. -

Dynamic Class Modification

Frameworks like Django and SQLAlchemy use introspection to scan your models and generate database tables automatically. You don’t explicitly tell Django, “This is a field”; it inspects the class, finds fields, and builds the SQL under the hood. -

Automated Testing

Testing frameworks likeunittestorpytestuse introspection to auto-discover test cases. For example,pytestlooks for functions starting withtest_without you having to register them manually.

Example:

import inspect

def hello(name):

return f”Hello {name}!”

print(inspect.signature(hello))

# (name)

The inspect module takes introspection to the next level: you can peek into function signatures, default values, docstrings, and even the source code.

👉 In short: introspection is the microscope of Python metaprogramming. It lets you analyze, explore, and even manipulate objects dynamically—which is exactly what we’ll build upon in the next sections (dynamic code execution, decorators, and metaclasses).

4. Dynamic Code Execution in Python

If introspection is about looking at code while it runs, then dynamic code execution is about generating brand-new code while your program is alive and making Python run it immediately. It’s like teaching your pet dog not just new tricks—but teaching it how to invent new tricks for itself. 🐶✨

In Python, the main culprits (er… tools) for this are eval() and exec(). Let’s dig into how they work, their quirks, and why you should use them carefully (spoiler: they can be as dangerous as giving scissors to a toddler).

4.1 The eval() Function

The eval() function literally evaluates a string as Python code and returns the result. Think of it as saying:

“Hey Python, pretend this string is real code—what’s the answer?”

Example:

expr = "3 * (4 + 5)"

print(eval(expr)) # 27

You can also give eval variables to play with:

x = 10

y = 5

print(eval("x * y")) # 50

Sounds powerful, right? But here’s the catch: eval will execute anything you give it. That’s fine when you’re the one writing the string, but if that string comes from user input… uh-oh.

⚠️ Security Danger:

user_input = "__import__('os').system('rm -rf /')"

eval(user_input) # Congrats, you just nuked your system.

👉 Lesson: Never, ever feed untrusted input into eval() unless you enjoy chaos.

4.2 The exec() Function

If eval() is about evaluating expressions that return a value, then exec() is about executing full chunks of Python code—even if they don’t return anything.

Example:

code = """

def greet(name):

return f"Hello, {name}!"

"""Notice the difference:

-

eval("3 + 4")→ returns 7. -

exec("x = 3 + 4")→ executes code, but doesn’t return anything.

exec() is your go-to when you want to generate new functions, classes, or modules on the fly.

But again, it’s dangerous if misused. Handing user input to exec() is basically letting strangers type directly into your terminal.

4.3 Practical Examples

Alright, enough theory. Let’s see how dynamic execution can actually be useful, not just terrifying.

a) Dynamically Creating Functions

def make_multiplier(n):

code = f"""

def multiply(x):

return x * {n}

"""

exec(code, globals()) # Define multiply in global scope

return multiplyprint(double(10)) # 20

Here we built a multiply function at runtime, customized to a factor. It’s like a function factory powered by exec().

b) Dynamic SQL Queries (Safely!)

Imagine building queries dynamically (dangerous with raw eval/exec, but useful with controlled templates):

import sqlite3

conn = sqlite3.connect(“:memory:”)

cursor = conn.cursor()

cursor.execute(“CREATE TABLE users (id INT, name TEXT)”)

# Safe parameterized query (don’t use eval here!)

name = “Alice”

cursor.execute(“INSERT INTO users VALUES (?, ?)”, (1, name))

cursor.execute(“SELECT * FROM users WHERE name=?”, (name,))

print(cursor.fetchall()) # [(1, ‘Alice’)]

⚡ Pro tip: When dealing with external input, always use safe templating or parameterized queries instead of raw eval/exec.

c) Meta Configurations and Scripting

Frameworks like Django and Flask sometimes generate Python code dynamically based on configs or models. exec() is one of the hidden gears under that machinery.

🧠 TL;DR of Dynamic Execution

-

eval()→ evaluates a string as an expression and returns the result. -

exec()→ executes full Python code dynamically, no return. -

Use cases: generating functions, dynamic DSLs, testing tools, automation.

-

⚠️ Risks: security nightmares if you use them with untrusted input. Always prefer templating engines, AST manipulation, or parameterized APIs when working with external input.

5. Decorators: The Gateway to Metaprogramming

If metaprogramming were a theme park, decorators would be the “easy ride” before you hop onto the scary rollercoaster of metaclasses. They’re approachable, super useful, and once you master them, you’ll start seeing them everywhere in Python—from Flask routes to Django views to your friendly @staticmethod.

Think of decorators like stickers you slap onto a function or class: they don’t change the original item, but they add some magical extra powers.

5.1 Introduction to Decorators

At their heart, decorators are just functions that wrap other functions.

Why does that work? Because in Python:

-

Functions are first-class citizens. (Meaning you can pass them around like variables, return them from other functions, and even modify them.)

-

Wrapping lets you extend or tweak behavior without touching the original code.

That means you can say:

@my_decorator

def greet():

return "Hello!"

And Python will secretly do:

def greet():

return "Hello!"So decorators are nothing more than syntactic sugar for “wrapping functions in other functions.”

5.2 Function Decorators

Let’s start small:

def logger(func):

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

print(f"Calling {func.__name__} with {args}, {kwargs}")

result = func(*args, **kwargs)

print(f"{func.__name__} returned {result}")

return result

return wrapperdef add(x, y):

return x + y

Output:

Calling add with (2, 3), {}

add returned 5

Now your boring add() function comes with built-in logging. This is the power of decorators: you don’t change the original function, but suddenly it’s way more useful.

Common decorator use cases:

-

Logging: Track what’s being called.

-

Authentication: Restrict access in web apps.

-

Caching: Store results to avoid recomputation.

Example: caching with functools.lru_cache:

from functools import lru_cache

@lru_cache(maxsize=100)

def fib(n):

if n < 2: return n

return fib(n-1) + fib(n-2)

print(fib(30)) # Way faster thanks to caching

5.3 Class Decorators

Yes, you can decorate entire classes, not just functions.

def auto_repr(cls):

def __repr__(self):

return f"{cls.__name__}({self.__dict__})"

cls.__repr__ = __repr__

return clsclass Person:

def __init__(self, name, age):

self.name, self.age = name, age

print(p) # Person({‘name’: ‘Alice’, ‘age’: 30})

Suddenly every instance of Person has a neat __repr__ without you writing it manually.

Frameworks like Django use class decorators under the hood to register models, views, and signals automagically.

5.4 Chained and Parameterized Decorators

Decorators can be stacked like pancakes 🥞:

def bold(func):

def wrapper():

return f"<b>{func()}</b>"

return wrapperdef wrapper():

return f”<i>{func()}</i>”

return wrapper

@italic

def hello():

return “Hello!”

Order matters! (Like syrup before butter or butter before syrup—choose wisely.)

And you can also make parameterized decorators:

def repeat(n):

def decorator(func):

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

for _ in range(n):

result = func(*args, **kwargs)

return result

return wrapper

return decoratordef cheer():

print(“Go Python!”)

# Go Python!

# Go Python!

# Go Python!

Here, repeat(3) returns a decorator that repeats the function 3 times.

🧠 Why Decorators Matter in Metaprogramming

Decorators show us the essence of metaprogramming: modifying code without changing the source. They give you:

-

Cleaner syntax (compared to manual wrapping).

-

Reusable building blocks (logging, caching, security).

-

Entry into higher metaprogramming concepts (like metaclasses).

That’s why decorators are often the gateway drug into the deeper world of Python metaprogramming. Once you’re comfortable with them, you’ll feel more confident tackling the big scary boss: metaclasses.

6. Metaclasses: The Core of Python Metaprogramming

If decorators are the “training wheels” of Python metaprogramming, then metaclasses are the full-blown motorbike 🚴💨. They’re often described as “classes of classes”—and yes, that sounds confusing at first. But don’t worry, by the end of this section you’ll be able to nod knowingly when someone drops the word metaclass at a meetup.

6.1 What is a Metaclass?

In Python:

-

Objects are instances of classes.

-

Classes themselves are instances of metaclasses.

Boom. Mind blown? Here’s a simple picture:

Object --> Class --> Metaclass

By default, Python uses type as the metaclass for all classes:

class Dog:

passprint(isinstance(Dog, type)) # True

So, just as you can control how instances are created in a class, metaclasses let you control how classes themselves are created.

Think of metaclasses as the architects of your classes.

6.2 Creating Custom Metaclasses

A custom metaclass is just a class that inherits from type. You can override __new__ and __init__ to customize class creation.

# Define a metaclass

class MyMeta(type):

def __new__(mcs, name, bases, namespace):

print(f"Creating class {name}")

return super().__new__(mcs, name, bases, namespace)class MyClass(metaclass=MyMeta):

pass

Output:

Creating class MyClass

What happened here?

-

When Python sees

class MyClass, it callsMyMeta.__new__. -

That gives you a chance to inject, validate, or transform the class before it exists.

6.3 Practical Use Cases of Metaclasses

Metaclasses sound abstract, but they actually power a ton of real-world tools:

1. Enforcing Coding Standards

Want to ensure every class has a docstring? A metaclass can enforce that:

class DocMeta(type):

def __new__(mcs, name, bases, namespace):

if "__doc__" not in namespace or not namespace["__doc__"]:

raise TypeError(f"Class {name} must have a docstring")

return super().__new__(mcs, name, bases, namespace)“””I have a docstring!”””

pass

# pass # ❌ Raises TypeError

This is how frameworks enforce consistency across huge codebases.

2. Automatic Class Registration

Want to build a plugin system where all subclasses are auto-registered? Easy with a metaclass:

class RegistryMeta(type):

registry = {}

def __new__(mcs, name, bases, namespace):

cls = super().__new__(mcs, name, bases, namespace)

if name != "Base":

mcs.registry[name] = cls

return clspass

class PluginB(Base): pass

# {‘PluginA’: <class ‘__main__.PluginA’>, ‘PluginB’: <class ‘__main__.PluginB’>}

Boom — automatic registration without any manual bookkeeping.

3. Singleton Pattern (Enforcing One Instance)

class SingletonMeta(type):

_instances = {}

def __call__(cls, *args, **kwargs):

if cls not in cls._instances:

cls._instances[cls] = super().__call__(*args, **kwargs)

return cls._instances[cls]pass

db2 = Database()

print(db1 is db2) # True

Metaclasses let you control instance creation at the class level, which is perfect for design patterns like Singleton.

6.4 Metaclasses vs Decorators: When to Use Which

A common question: Should I use a decorator or a metaclass?

-

Use a decorator when:

-

You want to modify a function or single class behavior in a lightweight way.

-

Example: logging, caching, auth wrappers.

-

-

Use a metaclass when:

-

You need to enforce rules or inject logic across many classes.

-

Example: ORM frameworks (Django’s models use metaclasses to map fields to database tables).

-

Think of it this way:

-

Decorators are like stick-on tattoos: fun, temporary, and specific.

-

Metaclasses are like genetic engineering: they fundamentally define what your classes are.

🧠 Why Metaclasses Matter

Metaclasses might feel esoteric, but they underpin some of Python’s most powerful frameworks:

-

Django ORM: Uses metaclasses to auto-generate SQL from model definitions.

-

SQLAlchemy: Dynamically constructs table mappings.

-

Pydantic: Builds data validation models at runtime.

Once you understand them, you’ll start spotting their fingerprints everywhere.

7. Code Generation Techniques in Python

So far, we’ve seen how introspection, dynamic execution, decorators, and metaclasses let you manipulate code at runtime. But what if you want Python to write entirely new code for you? That’s where code generation comes in.

There are multiple ways to do this — ranging from neat and safe (like templating engines) to wild and risky (like messing with bytecode). Let’s explore the spectrum.

7.1 Generating Functions Dynamically

The simplest way to generate code on the fly is to create functions dynamically. You can do this using closures or exec().

Using Closures:

def make_power(n):

def power(x):

return x ** n

return powercube = make_power(3)

print(cube(2)) # 8

Here, make_power is like a function factory — generating new functions tailored to a specific exponent.

Using exec() for Dynamic Functions:

def make_function(op):

code = f"""

def func(x, y):

return x {op} y

"""

namespace = {}

exec(code, namespace)

return namespace['func']print(adder(3, 4)) # 7

This is flexible but dangerous if op comes from untrusted input (imagine a malicious ; os.remove('*.py')). Always sanitize inputs!

7.2 Template-Based Code Generation

Sometimes you don’t want to handcraft strings of Python code. That’s where templating engines like Jinja2 come in handy.

Example: Generating Boilerplate

from jinja2 import Template

template = Template(“””

class {{ class_name }}:

def __init__(self, {{ fields|join(‘, ‘) }}):

{% for field in fields %}

self.{{ field }} = {{ field }}

{% endfor %}

“””)

code = template.render(class_name=“Person”, fields=[“name”, “age”])

print(code)

Output:

class Person:

def __init__(self, name, age):

self.name = name

self.age = age

Templating engines are widely used in web frameworks, but they’re also brilliant for generating Python classes, config files, or even SQL safely.

7.3 AST (Abstract Syntax Tree) Manipulation

For advanced cases, you can work directly with Python’s AST (Abstract Syntax Tree) — a structured representation of source code.

The ast module lets you:

-

Parse Python code into a tree.

-

Inspect or modify it.

-

Compile it back into executable code.

Example: Inspecting a Function

import ast

source = “””

def greet(name):

return “Hello ” + name

“””

tree = ast.parse(source)

print(ast.dump(tree, indent=4))

Output (simplified):

Module(

body=[

FunctionDef(

name='greet',

args=arguments(...),

body=[

Return(

BinOp(

left=Constant(value='Hello '),

op=Add(),

right=Name(id='name')

)

)

]

)

]

)

You can actually modify the AST and recompile it:

new_tree = tree

new_tree.body[0].name = "welcome" # Rename functionexec(code_obj)

This is how linters, code analyzers, and even transpilers (like converting Python to another DSL) work under the hood.

7.4 Bytecode Manipulation

If AST is like working with blueprints, then bytecode manipulation is like grabbing a screwdriver and tinkering directly with the engine.

Python compiles code into bytecode (instructions for the Python Virtual Machine). You can inspect it with the dis module:

import dis

def add(x, y):

return x + y

dis.dis(add)

Output (simplified):

2 0 LOAD_FAST 0 (x)

2 LOAD_FAST 1 (y)

4 BINARY_ADD

6 RETURN_VALUE

Yes, that’s Python broken down into its virtual machine instructions.

Can you modify bytecode? Yes. Should you? Only if you’re building tools like debuggers, profilers, or obfuscators — because it’s risky and non-portable. Libraries like bytecode or codetransformer can help.

🧠 Why Code Generation Matters

-

Productivity: Stop writing boilerplate; let Python write it for you.

-

Frameworks: Django, SQLAlchemy, and Pydantic rely on code generation for models and queries.

-

Dynamic Tools: From testing frameworks to CLI generators, code gen saves time.

-

AI & Data Science: Auto-generated ML pipelines often use templating and AST to adapt models dynamically.

But remember:

-

Start with templates or closures (safe).

-

Move to AST manipulation if you need precision.

-

Only touch bytecode if you really, really know what you’re doing.

8. Real-World Applications of Metaprogramming in Python

Metaprogramming might sound like something out of a computer science textbook, but you’ve already used it if you’ve worked with popular frameworks like Django, Flask, or Pydantic. These tools hide boilerplate from you and feel “magical” precisely because they leverage introspection, decorators, metaclasses, and code generation under the hood.

Let’s break down some major areas where Python’s “code that writes code” really shines.

8.1 Frameworks and Libraries

Django ORM Metaprogramming

Django models use metaclasses to map Python classes to database tables. When you write:

from django.db import models

class Person(models.Model):

name = models.CharField(max_length=50)

age = models.IntegerField()

Django doesn’t just store this as a plain Python class. Instead, it inspects the class attributes (via introspection) and uses a metaclass to register the fields, build SQL queries, and handle migrations.

That’s why you can later run:

Person.objects.create(name="Alice", age=30)

…without writing a single SQL statement yourself.

SQLAlchemy Dynamic Class Creation

SQLAlchemy takes a similar approach but goes even deeper: it dynamically builds Python classes based on database schemas, so you don’t have to define them manually.

from sqlalchemy import Column, Integer, String, create_engine, MetaData, Table

from sqlalchemy.orm import mappermetadata = MetaData()

Column(“id”, Integer, primary_key=True),

Column(“name”, String)

)

metadata.create_all(engine)

Now User magically has attributes id and name mapped to the database. This is metaprogramming in action.

Pydantic Model Generation

Pydantic (used in FastAPI) dynamically generates validators for your data models.

from pydantic import BaseModel

class User(BaseModel):

id: int

name: str

u = User(id=“42”, name=“Alice”)

print(u) # id=42 name=’Alice’

Even though you passed "42" (a string), Pydantic auto-generated conversion code to coerce it into an integer. That’s introspection + runtime code execution baked in.

8.2 Use in Data Science & AI

Metaprogramming isn’t just for web frameworks — it’s a lifesaver in data-heavy workflows too.

Auto-Generating ML Pipelines

Libraries like scikit-learn’s Pipeline let you stitch together preprocessing steps dynamically. But more advanced ML frameworks (like AutoML tools) generate entire pipelines on the fly by inspecting your data.

Example: dynamic feature engineering:

features = ["age", "income", "city"]

def make_feature_class(fields):

attrs = {f: None for f in fields}

return type(“FeatureSet”, (object,), attrs)

FeatureSet = make_feature_class(features)

fs = FeatureSet()

fs.age, fs.income, fs.city = 30, 50000, “NYC”

print(fs.__dict__)

# {‘age’: 30, ‘income’: 50000, ‘city’: ‘NYC’}

Here we generated a class dynamically based on a dataset’s features — a mini version of what AutoML systems do.

Dynamic Model Generation in AI

Frameworks like Hugging Face Transformers use metaprogramming to dynamically register new model architectures, so adding new NLP models is painless. Instead of rewriting giant boilerplate classes, you can just subclass and the framework wires up the rest.

8.3 Use in DevOps & Automation

DevOps tools love metaprogramming because infrastructure is full of repetitive patterns. Why write the same YAML or config 100 times when you can auto-generate it?

Auto-Generating Config Files

Imagine you need 20 Kubernetes deployment files with only small variations. Instead of manually typing YAML until your fingers fall off, you can use Jinja2 templates or even Python metaclasses to generate them dynamically.

from jinja2 import Template

template = Template(“””

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: {{ name }}

spec:

containers:

– name: app

image: {{ image }}

“””)

print(template.render(name=“myapp”, image=“nginx:latest”))

Boom, a YAML file created dynamically — one template, infinite deployments.

Dynamic CLI Tools

Libraries like click and argparse often use introspection to automatically build CLI commands from functions. With just a few decorators, you suddenly have a fully working CLI without touching parsing logic:

import click

@click.command()

@click.option(“–name”, prompt=“Your name”)

def greet(name):

click.echo(f”Hello {name}!”)

if __name__ == “__main__”:

greet()

Behind the scenes, click uses metaprogramming to inspect the function signature (name argument) and auto-generate the CLI options.

🧠 Why This Matters

These examples prove that metaprogramming isn’t just an academic exercise: it’s the engine behind Python’s best frameworks. The reason Django feels magical, Pydantic feels effortless, and DevOps tools feel scalable is because they leverage code that writes code.

The real-world takeaway:

-

Web development: ORMs and validation rely on metaclasses & decorators.

-

Data science/AI: AutoML and model generation thrive on dynamic code execution.

-

DevOps/Automation: Configs, pipelines, and CLI tools use templating & introspection.

9. Best Practices in Python Metaprogramming

Metaprogramming is like nitroglycerin: incredibly powerful, but one wrong move and… 💥. That’s why great Pythonistas don’t just know how to use it — they know when not to.

Here are some guiding principles to keep your metaprogramming code genius-level instead of gremlin-level.

9.1 Readability vs Magic

Python has a famous motto:

“Explicit is better than implicit.”

Metaprogramming is inherently implicit — code that writes code can be hard to follow. That’s why you should always ask: Is this clever trick really worth it?

Bad magic:

def spell(name):

return lambda x: f"{name} says {x}!"Good enough for a code golf competition, but terrible for maintainability.

Better: write the extra two lines and keep things clear.

👉 Rule of thumb: if future-you (or your teammate) won’t understand it in six months, don’t do it.

9.2 Documentation and Testing

When you generate code dynamically, it doesn’t show up in your source files — so without documentation, it’s invisible.

What to do:

-

Add docstrings that explain the “magic” parts.

-

If you’re auto-generating classes or functions, document the rules (e.g., “All models must define a

Metaclass with fields”). -

Use testing frameworks to validate the generated code.

Example:

def make_adder(n):

"""Dynamically generates an adder function that adds n to its input."""

def adder(x):

return x + n

return adder

This makes it clear what the generator function does without having to dig through the implementation.

9.3 Performance Considerations

Metaprogramming often runs at runtime, which can mean extra overhead if you’re not careful.

Example: Expensive Introspection

import inspect

def slow_func(f):

sig = inspect.signature(f) # costly if repeated

…

If you run this thousands of times in a loop, it’s going to slow you down.

Solutions:

-

Cache results (memoization,

functools.lru_cache). -

Generate code once, reuse many times.

-

Avoid unnecessary introspection in performance-critical sections.

9.4 Security Concerns

We’ve already seen the dangers of eval() and exec(). These two are the chainsaws of Python: useful in skilled hands, catastrophic in careless ones.

Golden rules:

-

Never pass untrusted input to

eval/exec. -

Use safe alternatives:

-

AST parsing: Validate code before running.

-

Templates: Use Jinja2 or f-strings, not raw

eval. -

literal_evalfromast: Safe parsing of Python literals (strings, numbers, tuples, dicts).

-

Example:

import ast

safe_data = ast.literal_eval(“{‘name’: ‘Alice’, ‘age’: 30}”)

print(safe_data) # {‘name’: ‘Alice’, ‘age’: 30}

This prevents arbitrary code execution — it only parses literals, not functions or system calls.

🧠 The Best Practice Mindset

Think of metaprogramming as a scalpel, not a hammer:

-

Use it to remove boilerplate cleanly.

-

Avoid it when plain old Python is clearer.

-

Document it like you’re explaining to a curious intern.

-

Test it like you don’t trust it (because you shouldn’t at first).

When used wisely, metaprogramming makes your codebase elegant and scalable. When abused, it becomes the stuff of horror stories told at 2am debugging sessions.

10. Limitations of Metaprogramming in Python

Metaprogramming makes Python elegant and powerful, but it isn’t a silver bullet. In fact, sometimes it can feel like you’ve summoned a helpful genie… who also leaves a mess in your living room. Let’s unpack the main challenges.

10.1 Performance Bottlenecks

Metaprogramming often involves runtime work: introspection, reflection, and dynamic code generation. Unlike C++’s compile-time templates (which shift the burden to compilation), Python usually does the heavy lifting while your program is running.

This means:

-

Repeated

inspect,dir(), or dynamic class creation can slow things down. -

execandevalcarry overhead in addition to their security risks. -

Generated code can be harder for Python’s interpreter (CPython) to optimize.

👉 In high-performance environments (finance, gaming, real-time systems), excessive metaprogramming is often avoided in favor of plain, optimized code.

10.2 Debugging Challenges

Metaprogramming creates invisible code paths. The function you’re debugging might not even exist in your source — it could have been created at runtime.

Ever stepped through a stack trace that says:

<function dynamically_generated_function at 0x7ff...>

…and thought, what on Earth is this thing?

That’s the pain of debugging metaprogramming-heavy projects. Tools like IDEs and linters also struggle, since they rely on static analysis.

10.3 Maintainability Concerns

The cleverer your code looks today, the more painful it may be tomorrow. Metaprogramming can quickly turn a neat trick into an unreadable jungle.

Teams often complain that:

-

Junior devs struggle to understand what’s going on.

-

Adding new features feels risky because the “magic” might break.

-

Code reviews become debates over sorcery instead of design.

👉 Translation: your metaprogramming should always serve clarity, not ego.

10.4 Comparison with Other Languages

Python is powerful, but it’s not the undisputed champion of metaprogramming.

-

C++: Template metaprogramming allows complex compile-time computations, producing highly optimized machine code. Downside? Templates can make error messages look like Shakespearean tragedies.

-

Lisp: Famous for macros — Lisp’s metaprogramming is arguably cleaner and more native than Python’s. Code and data share the same structure (S-expressions), so manipulating code is seamless.

-

Ruby: Metaprogramming is deeply integrated. Ruby developers often rely on

method_missing,define_method, and open classes to dynamically shape objects.

Python sits in the middle: more approachable than C++ templates, less “everything is a macro” than Lisp, and slightly more restrained than Ruby.

🧠 Key Takeaway

Metaprogramming in Python is like caffeine:

-

A little boosts productivity.

-

Too much, and you’ll be jittery, unfocused, and regretting your life choices.

So while Python’s code that writes code is amazing, its limitations — performance hits, debugging nightmares, maintainability risks, and language constraints — mean you should always weigh whether it’s truly the right tool for the job.

11. The Future of Metaprogramming in Python

Metaprogramming in Python has always been about stretching the language — using introspection, decorators, and metaclasses to make the interpreter dance. But Python, like any good wizard, keeps learning new tricks.

Here’s where things are heading:

11.1 Python 3.12+ and Beyond: Better Introspection & Typing

Recent Python versions have doubled down on type hints and runtime type inspection. With PEPs like:

-

PEP 563 (postponed evaluation of annotations).

-

PEP 646 (variadic generics).

-

PEP 695 (generic classes and type parameter syntax in Python 3.12).

These improvements mean metaprogramming tools (like Pydantic or FastAPI) can generate and validate models more reliably.

👉 Translation: You’ll soon be able to write cleaner metaclasses and decorators that play nicely with static type checkers like MyPy and Pyright. Less magic, more trust.

11.2 AI Meets Metaprogramming

Remember when “code that writes code” sounded sci-fi? Well, AI has crashed the party. Large Language Models (👋 hi, that’s me) and AutoML frameworks are now generating boilerplate code, data pipelines, and even entire test suites.

Metaprogramming will likely evolve into AI-assisted coding, where:

-

AI generates dynamic functions or classes.

-

Human devs define rules and constraints.

-

The machine does the repetitive wiring.

This shifts metaprogramming from manual wizardry to collaboration with intelligent tools.

11.3 “Self-Writing” Code in ML Pipelines

In Machine Learning, pipelines often need to adapt on the fly: new features, new data sources, new preprocessing steps. Instead of hand-coding, future ML frameworks could:

-

Introspect the dataset.

-

Dynamically generate preprocessing steps.

-

Build, train, and tune models automatically.

In other words: pipelines that metaprogram themselves. Think scikit-learn pipelines that say, “I noticed your new feature column, I’ll generate the normalization step and plug it in.”

11.4 Safer Dynamic Code Execution

The Python community knows eval() and exec() are dangerous but sometimes unavoidable. Expect more sandboxed execution environments and safer alternatives built into the standard library.

Possible future:

from safe_exec import sandbox

sandbox.run(“print(‘Hello!’)”)

This could allow metaprogramming without the constant paranoia of remote code injection.

11.5 Declarative Metaprogramming

Frameworks like SQLAlchemy, Django ORM, and TensorFlow have already shown the power of declarative style: you describe what you want, and the framework generates the code.

Future Python metaprogramming might lean even more declarative, making “describe and let Python build it” the default. This would blend the readability of high-level DSLs (domain-specific languages) with the flexibility of runtime generation.

11.6 Beyond Python: Interoperability

Python’s role as the “glue language” of tech means its metaprogramming might stretch into other ecosystems:

-

Cross-language AST manipulation (e.g., Python generating optimized Rust or C++ code).

-

Metaprogramming for WebAssembly (Python generating browser-executable code dynamically).

-

Interfacing with AI model DSLs (like TorchScript or ONNX) through Python codegen.

🧠 The Big Picture

Metaprogramming in Python is moving from clever tricks for hackers → core tools for production frameworks → AI-assisted automation at scale.

In the future:

-

Python devs will spend less time writing boilerplate.

-

AI and frameworks will handle much of the “meta” work.

-

Humans will focus more on rules, architecture, and creativity.

Which means metaprogramming could shift from being “that cool advanced feature” to the default way we build large-scale Python systems.

12. Conclusion

We started this journey by asking a bold question: what if your code could write more code for you? That’s the essence of Python metaprogramming — bending the language so your programs can adapt, extend, and even generate themselves.

Along the way, we explored:

-

The core idea: Metaprogramming lets you manipulate classes, functions, and objects at runtime.

-

The tools: Introspection, dynamic execution (

eval,exec), decorators, and the mighty metaclasses. -

The applications: Frameworks like Django, SQLAlchemy, and Pydantic thrive because they lean heavily on metaprogramming.

-

The dark side: Performance hits, debugging nightmares, and maintainability risks if you go overboard.

-

The future: Python 3.12+ improving typing, safer execution models, declarative frameworks, and even AI-assisted “self-writing” code.

So… what’s the verdict?

Metaprogramming in Python is a superpower. Used well, it saves you hours of boilerplate, makes frameworks smarter, and opens up programming possibilities that feel almost magical. But, like any superpower, it comes with responsibility. Too much “magic” and your codebase becomes an incomprehensible spellbook that nobody else wants to maintain.

👉 The trick is balance:

-

Use metaprogramming where it adds clarity, flexibility, or removes redundancy.

-

Avoid it when plain old Python will do just fine.

-

Document your meta-code generously (future you will thank you).

-

Always keep security, readability, and performance in mind.

If you’re new to this, start small. Play around with decorators (they’re the friendliest entry point). Then peek at metaclasses, explore the ast module, or even try generating functions dynamically. Treat it like learning a new language inside Python itself — one where the subject is not just data, but the code you write.

And who knows? The next great Python framework — the “Django of tomorrow” — might just come from your experiments with code that writes code.

So go forth, experiment wisely, and remember: in the kingdom of programming, those who master metaprogramming aren’t just writing code… they’re teaching Python how to write it for them.

13. Additional Resources

Learning metaprogramming in Python isn’t a “read one article, become a wizard” journey — it’s a path of continuous exploration. If today’s guide got you curious, here are some top-notch resources to keep sharpening your metaprogramming skills.

📖 Official Python Documentation

-

Python Data Model — A must-read for understanding how objects, classes, and metaclasses really work under the hood.

-

inspect module — Your gateway to introspection in Python.

-

ast module — Learn how to analyze and manipulate Python code as Abstract Syntax Trees.

-

functools — Essential when building decorators and higher-order functions.

📦 Popular Libraries Leveraging Metaprogramming

-

Django ORM — Uses metaclasses to generate database models dynamically.

-

SQLAlchemy — Heavy use of declarative metaprogramming for database mappings.

-

Pydantic — Dynamically creates data validation models from type hints.

-

Click — A neat CLI framework that leverages decorators to generate command-line interfaces.

These libraries are living, breathing examples of metaprogramming in production — studying them is like peeking into a wizard’s spellbook.

📚 Books & Tutorials

-

Fluent Python by Luciano Ramalho — The definitive deep dive into Python’s advanced features (decorators, metaclasses, and more).

-

Python Cookbook by David Beazley & Brian K. Jones — Great for practical recipes, including some “meta” tricks.

-

Metaprogramming in Python (various blog series/tutorials) — Search for community-written guides; many go step-by-step through decorators and metaclasses with real-world use cases.

🎓 Tutorials & Talks

-

PyCon talks on metaprogramming and decorators (search YouTube for gems like David Beazley’s presentations).

-

Real Python’s tutorials on decorators and metaclasses.

🧠 Final Thought

Remember: metaprogramming isn’t about showing off. It’s about writing less repetitive code, automating patterns, and making Python do the boring stuff so you can focus on the creative parts of problem-solving. Use these resources to dive deeper, experiment with small projects, and then — when you’re ready — build something that makes others say: “Wait… Python can do that?!”