Learn beautiful Animations in PowerPoint – Click Here

Learn Excel Skills – Click Here

Learn Microsoft Word Skills – Click Here

If you’ve ever stared at a Python error saying “NameError: name ‘x’ is not defined” and muttered, “But I literally defined x right there!” — congratulations, you’ve officially met Python’s mischievous little gremlin: scope.

And its equally mysterious sidekick? Namespace.

Together, these two decide who gets to see what variable, when, and for how long. Like bouncers at a nightclub, they control who gets in (and who gets thrown out with an error message).

So what’s all the fuss about?

When you write Python code, you’re constantly creating, accessing, and modifying names — variables, functions, classes, modules, you name it. But have you ever wondered:

-

Where does Python store all those names?

-

How does it know which “x” you’re referring to when there’s more than one?

-

And why does it sometimes act like it has amnesia about your variables?

That’s where scope and namespace come in.

🧩 What is a Namespace?

Think of a namespace as a big labeled box (or more accurately, a dictionary) that maps names → objects.

So when you do this:

Python stores the name x in a namespace and points it to the object 42.

Different namespaces exist at different levels — like global, local, or even built-in — and Python keeps them nicely separated to avoid chaos (mostly).

🔍 What is Scope?

Scope is the region of the code where a name is recognized. It’s like saying:

“This variable lives here — outside this zone, it doesn’t exist. Don’t ask for it, don’t look for it.”

Scopes help Python stay organized and efficient, making sure your variables don’t randomly bump into each other across functions and modules.

🎯 The Goal

In this article, we’re going to demystify Python’s LEGB rule — the magical four-layer logic Python uses to decide which variable to use when multiple exist.

By the end, you’ll:

-

Understand how Python looks up names (and why it sometimes fails).

-

Learn to use

globalandnonlocalwithout accidentally nuking your variables. -

Laugh (a little), learn (a lot), and maybe even stop fighting with

NameError.

So buckle up, grab your favorite debugging snack, and let’s crack open the mysterious world of Python scope and namespace — once and for all.

🗂️ Understanding Namespaces in Python (aka: Where Python Keeps Your Stuff)

If Python were a person, it’d have an impeccable filing system — color-coded folders, neatly labeled drawers, and zero tolerance for misplaced names. That system? Namespaces.

When you type something like:

Python doesn’t just magically remember answer — it stores that name in a namespace, which is basically a map from names to objects.

Think of a namespace as a Python phonebook, where every name (like answer) points to the right object (like the integer 42). Need to call it later? Python looks it up in the book.

🧭 So, What Exactly Is a Namespace?

A namespace in Python is a dictionary-like structure that maps names (identifiers) to objects. It’s what lets Python know that print refers to a built-in function, not your cat’s name.

If we peek inside, namespaces look like this:

Python is constantly juggling multiple such dictionaries behind the scenes. The beautiful part? You rarely need to think about it… until something goes wrong.

📘 Real-World Analogy: The Office Drawer System

Imagine you work in an office (sorry, remote warriors, just bear with me).

-

You have a global drawer for all office-wide supplies.

-

You have your personal desk drawer where you keep your pens.

-

Inside that, maybe a mini drawer for secret snacks (no judgment).

-

And finally, there’s a corporate supply closet shared by everyone in the company.

Each drawer is separate — but you can reach into broader drawers if you need something. That’s exactly how namespaces work in Python.

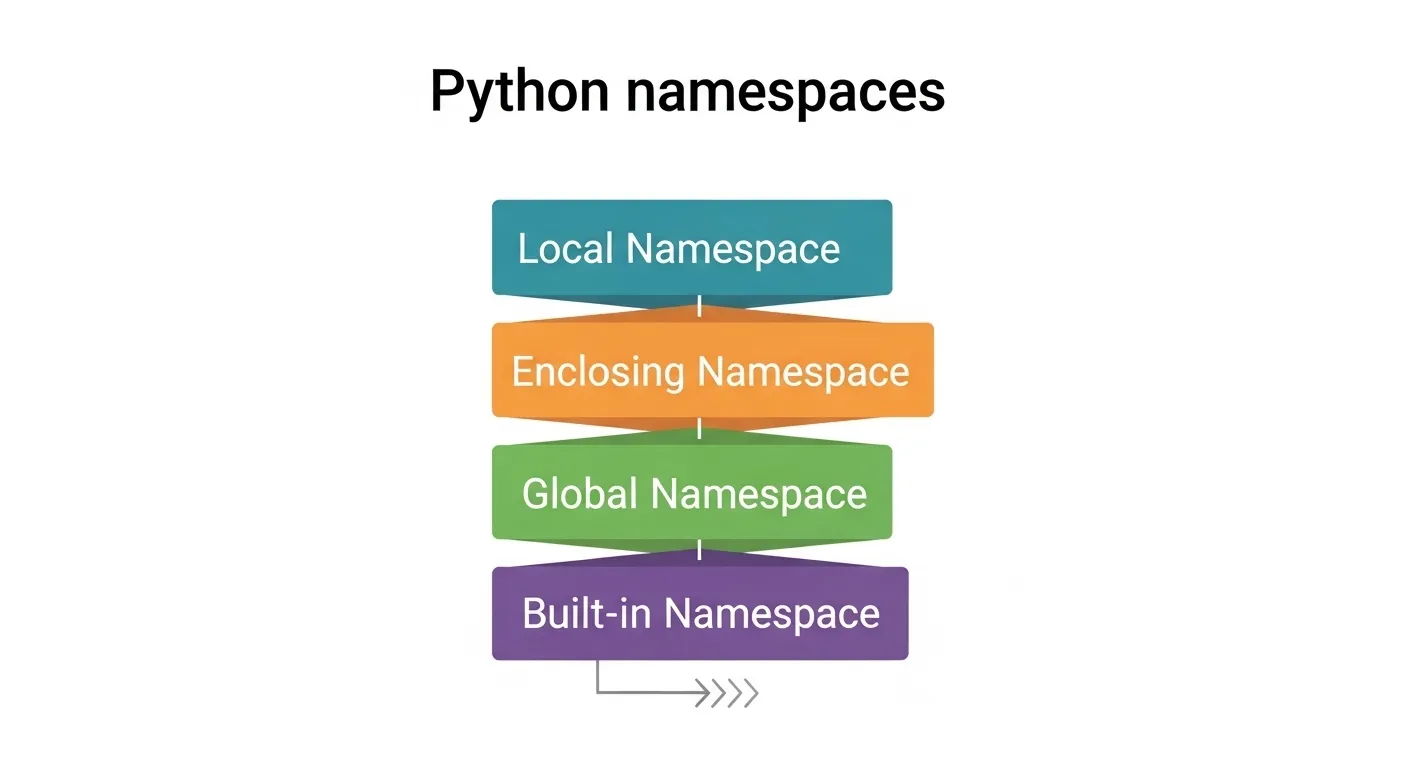

🧩 Types of Namespaces in Python

Python has four major types of namespaces, each created at different moments in your program’s life.

1. Built-in Namespace

-

Created when Python starts.

-

Contains all the built-in names you know and love — like

len,print,max, andException. -

Always available everywhere.

Example:

2. Global Namespace

-

Created when a module (your .py file) is run or imported.

-

Stores names you define at the top level of your script.

Example:

Here, both x and foo live in the global namespace of your script.

3. Enclosing Namespace

-

Exists when you have nested functions.

-

The outer function’s namespace is “enclosing” for the inner one.

Example:

4. Local Namespace

-

Created when a function is called.

-

Contains names defined inside that function (parameters, variables, etc.).

Example:

name exists only inside greet() — outside, Python pretends it never existed.

🧠 Under the Hood: How Python Stores Namespaces

Technically, Python stores namespaces as dictionaries. You can peek at them using globals() and locals().

Example:

Output (abridged):

globals() shows what’s available at the module level, while locals() shows what’s inside the current function.

⏳ Namespace Lifecycle: They Don’t Live Forever

-

The built-in namespace lives as long as the Python interpreter.

-

The global namespace lasts as long as your script runs.

-

The local namespace is born when a function is called… and dies as soon as the function ends (RIP temporary variables).

You can think of local namespaces as mayflies — short-lived, but essential for keeping things tidy.

💬 Wrapping Up

Namespaces are Python’s internal labeling system. They prevent name collisions, make debugging saner, and help your code run like an organized library, not a chaotic garage.

Next time Python says something isn’t defined, remember — maybe you’re just looking in the wrong namespace.

🔦 Understanding Scope in Python (Where Your Variables Actually Live)

Imagine you’re at a party 🥳. There’s a buffet, a bunch of rooms, and everyone’s name-tagged. You can grab snacks from your room, maybe peek into the kitchen, but you can’t just waltz into the DJ booth and grab their playlist.

That’s scope — Python’s way of saying,

“You can’t touch that variable; it’s not in your area.”

🧩 What Is Scope in Python?

In simple terms, scope is the region of your code where a variable is recognized. It determines where you can access a name — and where Python pretends it doesn’t exist.

So when you get that infuriating

it’s not that Python forgot — it’s just politely telling you, “Sorry, wrong room, that variable doesn’t live here.”

🧠 The Nerdy Definition (That Actually Makes Sense)

When Python compiles your code, it determines the scope of every variable — not while running, but at compile time.

That means when Python reads your code, it decides:

-

“Okay, this one’s local.”

-

“This one’s global.”

-

“This one belongs to that outer function.”

So by the time your code runs, the scoping map is already set in stone.

⚙️ Why Does Scope Matter?

Because without it, your program would descend into variable chaos — every function would overwrite everything else.

Scope helps Python:

-

Keep variables organized (no name collisions).

-

Make memory usage efficient.

-

Improve debugging and code clarity.

It’s basically Python’s personal assistant — ensuring your variables don’t start beef with each other.

🧪 Python’s Lexical (Static) Scoping

Python uses something called lexical scoping (or static scoping). That means the scope of a variable is determined by where it’s written in your code, not where it’s called from.

Let’s see it in action 👇

Output:

Here’s what happened:

-

Inside

test(), Python saw anotherxdefined locally (so it used that). -

Outside the function, Python used the global

x. -

No overlap, no confusion, just clean separation of scope zones.

So when you write a function, Python literally bakes in the scope based on the layout of your code — not where you call the function later.

🧩 Local vs Global Scope

Let’s break this down:

🔸 Local Scope

Variables created inside a function.

They vanish the moment the function ends.

Example:

Python: “Sorry, message doesn’t exist outside greet().”

🔸 Global Scope

Variables defined outside any function or class.

They’re accessible anywhere inside that file (unless shadowed).

Example:

But beware — if you try to reassign a global variable inside a function without the global keyword, Python assumes you’re making a new local one instead. That’s where a lot of beginner headaches start (more on that in Section 5).

⚡ Quick Debug Tip

If you ever wonder what’s currently in your local or global scope:

It’s like opening Python’s backstage pass — you can literally see all the names it knows about at that moment.

🧘 The Zen of Scope

Think of scope as your Python code’s boundaries of awareness.

-

Inside a function? That’s its own little universe.

-

Inside a nested function? You’ve got a universe within a universe.

-

Outside everything? Welcome to the global cosmos.

Understanding this is what separates Python users from Python masters.

💬 TL;DR

| Scope Type | Where Defined | When Alive | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local | Inside function | During function execution | Function variables |

| Enclosing | Outer function (in nested funcs) | As long as outer function exists | Closure vars |

| Global | Module level | Whole runtime | Module vars |

| Built-in | Python runtime | Always | len, print, etc. |

Scope is what keeps your variables behaving like polite roommates instead of territorial raccoons.

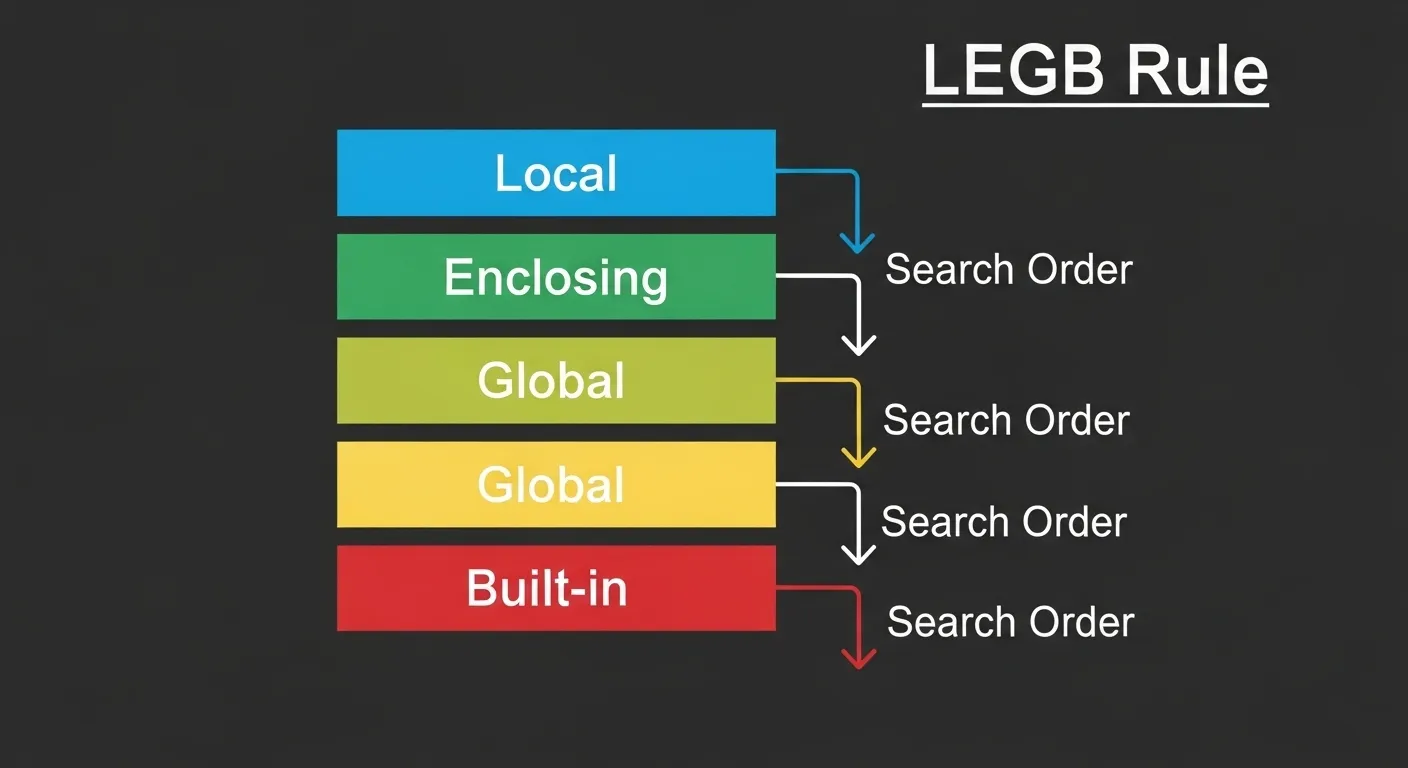

⚖️ The LEGB Rule Explained: Python’s 4-Layer Detective Story

If Python were a detective, it wouldn’t immediately panic when you mention a name like x.

Instead, it calmly lights a metaphorical pipe 🕵️♂️, squints at your code, and starts investigating through four neighborhoods in a very specific order:

L → E → G → B

Local → Enclosing → Global → Built-in

That’s the LEGB rule, the sacred law of Python’s variable lookup universe.

🧩 What Is the LEGB Rule?

Whenever Python sees a name (like x or result) in your code, it doesn’t just randomly guess where it came from.

It searches methodically in this order:

-

Local (L) — variables inside the current function.

-

Enclosing (E) — variables in any outer (but non-global) functions.

-

Global (G) — variables defined at the top level of your module/script.

-

Built-in (B) — Python’s built-in names like

len,print,Exception, etc.

If Python doesn’t find your variable after checking all four?

💥 Boom — NameError.

🧠 1. Local Scope (L): The Current Function

Python’s first stop is the local namespace — the current function you’re in.

Here, name is local to the function greet(). Try accessing it outside, and Python will look at you like,

“Who’s Alice?”

If a variable exists locally, Python doesn’t bother checking anywhere else. Local always wins the lookup race.

🧭 2. Enclosing Scope (E): Outer Function (in a Closure)

When you nest functions, the outer function becomes the enclosing scope for the inner one.

Here’s what happens:

-

inner()doesn’t have its owngreeting. -

Python checks the enclosing function

outer()and finds it there. -

Case closed — variable found in the Enclosing scope.

This is why closures work in Python — they remember the variables from their outer (enclosing) environment.

🌍 3. Global Scope (G): The Module Level

If Python can’t find the name locally or in an enclosing scope, it heads to the global scope — variables defined at the top level of your module (your .py file).

If you want to modify that global variable from inside a function, though, you’ll need to use the global keyword — but don’t worry, we’ll cover that mess in the next section.

🌈 4. Built-in Scope (B): Python’s Default Toolbox

Finally, if all else fails, Python checks the built-in namespace — basically, the “final boss” level of name searching.

This includes all those standard names like len, range, max, sum, print, etc.

Example:

These live in the builtins module, which Python automatically loads.

If you really want to peek inside, try this:

(Warning: It’s a long list — Python has a lot of built-in toys.)

😱 What Happens When Python Can’t Find the Name?

If Python finishes checking Local → Enclosing → Global → Built-in and still finds nothing…

That’s Python’s way of saying,

“I looked everywhere, buddy. No

thingyhere.”

So next time that error pops up, you can channel your inner detective and trace which part of the LEGB chain failed you.

🧨 Common Example: Variable Shadowing

Let’s throw a wrench into the gears — what if you redefine a built-in name?

Oops. You just shadowed (overwrote) the built-in len function with an integer.

Python did find len — but in your global scope, not in built-in.

That’s why understanding the LEGB order matters.

Pro tip: Don’t name your variables after built-ins. No one wants to debug that horror.

🪄 Visualizing the LEGB Search Path

Here’s how Python hunts for variables, Sherlock Holmes style 🕵️:

Python starts from the bottom (Local) and climbs up until it finds the name.

🧩 Quick Code Recap

Output:

See? LEGB in action — clean, predictable, elegant.

🧘♂️ Final Thoughts

The LEGB rule is like Python’s spiritual mantra.

Once you grasp it, so many “why isn’t this working” mysteries suddenly make sense.

It tells you where Python looks for names and why some variables seem to disappear into the void.

Next time you debug, visualize that LEGB ladder — Python always follows it, one step at a time.

🌍 Working with Global and Nonlocal Keywords: How to (Safely) Break the Rules

If Python variables lived in a peaceful village, the global and nonlocal keywords would be the nosy neighbors who occasionally jump fences to borrow sugar. They don’t always follow the rules — but sometimes, they’re exactly what you need.

⚡ The global Keyword

Let’s start with the troublemaker of the duo: global.

By default, when you assign a variable inside a function, Python assumes it’s local — even if there’s a global variable with the same name.

Example:

Result:

Python sees that you’re assigning to count, so it treats it as a local variable, even though you probably meant to modify the global one.

🧠 Using global to Modify Global Variables

To tell Python, “Hey, I’m talking about the one outside!”, use the global keyword.

Now Python knows: you’re referring to the global count, not creating a new local version.

⚠️ When to Use (and When to Avoid) global

✅ Use it when:

-

You need to maintain global state (like a config or counter).

-

You’re writing small scripts or quick prototypes.

🚫 Avoid it when:

-

You’re working on large projects (global state becomes chaos fast).

-

You can pass variables as function arguments instead — it’s cleaner.

global variables can make debugging painful, because any function can secretly change them. That’s how bugs sneak in wearing sunglasses. 😎

🌀 The nonlocal Keyword

Now, let’s meet the lesser-known cousin — nonlocal.

This one’s used inside nested functions to modify variables that belong to the enclosing scope (the “E” in LEGB).

Without it, Python treats assignments as local, even inside closures.

Example:

Same problem — Python thinks you’re trying to assign to a local count, not the one from outer().

🧙 Using nonlocal to Access Enclosing Variables

Enter nonlocal:

Output:

Now inner() successfully updates count from the enclosing outer() scope.

This is the secret sauce behind closures — functions that remember values from their outer scope.

🧩 global vs nonlocal: The Showdown

| Feature | global |

nonlocal |

|---|---|---|

| Modifies variable from | Global/module scope | Enclosing (non-global) scope |

| Common use case | Modify global state | Modify closure variables |

| Available in | Any function | Only nested functions |

| Example | Change global counter | Maintain state in closure |

💣 Common Mistakes

-

Using

globalwhen you meantnonlocal:

You’ll end up creating or modifying a completely different variable. -

Overusing globals:

Global variables turn your code into spaghetti — tasty but impossible to untangle. 🍝 -

Forgetting to declare before assignment:

Python won’t guess your intention; always declare withglobalornonlocalbefore using the variable.

🧘 Best Practices for Using global and nonlocal

-

Prefer returning values and passing them as arguments.

-

Reserve these keywords for cases where you really need shared state.

-

Document any global or nonlocal usage — future-you will thank you.

-

In larger projects, consider using classes or config objects instead of globals.

🧩 Example: Safe Global Configuration

That’s a cleaner (and more explicit) use of a global variable.

You’re changing the contents, not the reference itself — a subtle but important difference.

💬 In Summary

global and nonlocal are your power tools for managing scope — but like power tools, they can cause chaos if misused.

-

globalreaches up to the top of your code’s world. -

nonlocalreaches sideways into the nearest enclosing function. -

Both break normal scope barriers — so wield them wisely, young Padawan 🧘♂️.

💥 Common Errors and Pitfalls: How Python Scope Can Betray You

1. The Dreaded UnboundLocalError

Let’s start with the classic.

You’ve got a global variable. You want to update it inside a function. Easy, right?

Output:

Why does Python do this to you?

Because the moment it sees an assignment to count, it assumes you’re creating a local variable, not referring to the global one.

But then — plot twist — there’s no local count yet!

Fix: Declare it global:

Or better yet, avoid globals altogether and return the new value instead.

🕳️ 2. Shadowing Variables

Variable shadowing happens when you reuse a variable name that already exists in another scope.

Output:

You might think you changed x, but nope — you just made a different x.

Python doesn’t get mad about this; it just quietly lets you shoot yourself in the foot.

🧠 Pro tip: Use descriptive names (count_local, total_sum, global_count) to avoid this silent confusion.

🧨 3. Overwriting Built-in Names

This one’s sneaky — and oh-so-common.

You just overwrote the built-in list with an integer.

Python did nothing wrong — you did. It happily followed LEGB and found your local list, not the built-in one.

Fix: Never name variables list, str, int, max, or sum. Unless you enjoy debugging existential crises.

🌀 4. Mutable Type Confusion

Another classic trap: misunderstanding how mutable objects behave across scopes.

Output:

You didn’t declare data as global — yet it changed! Why?

Because you didn’t reassign data; you modified the existing object.

Scope rules only apply to variable assignment, not to mutation of objects like lists and dicts.

If you had reassigned it, like this:

That would have created a local data instead.

🧩 Lesson: Mutations go through, reassignments don’t — unless you say global.

🧟 5. Forgetting Function Boundaries

Beginners often expect variables from one function to exist in another:

Each function has its own local namespace. x lives and dies inside foo().

If you need to share data, use returns, parameters, or closures, not wishful thinking.

🧘 Bonus: Debugging Scope Issues Like a Pro

If you’re ever confused about what’s visible where, drop these inside your functions:

You’ll see exactly which variables Python can access — no psychic powers required.

💬 In Short

| Mistake | What Happens | Fix |

|---|---|---|

UnboundLocalError |

Assigning before declaring global |

Use global or avoid reassignment |

| Shadowing | Local variable hides outer one | Use distinct names |

| Overwriting built-ins | Lose access to built-in functions | Never reuse names like list, str, etc. |

| Mutable confusion | Objects mutate unexpectedly | Understand assignment vs mutation |

| Function boundaries | Variables don’t carry over | Return or pass as arguments |

Remember: Python isn’t being mean — it’s just following the rules (very strictly).

Once you internalize how scope and namespace work, these “pitfalls” turn into “ohhhh, I get it now!”

🚀 Advanced Topics: Deep Diving into Python Scope and Namespace Magic

Most Python tutorials stop after LEGB and call it a day.

But you’re not “most Python learners,” are you?

So let’s pop open the hood and see what’s really going on behind that smooth, dynamic, totally Zen scoping system.

🧘 Lexical Scope vs Dynamic Scope

Python uses lexical (or static) scope, which means where you write the variable matters — not where you call it from.

Let’s see:

Output:

💡 Why?

Because Python remembers that x from the enclosing function at definition time, not at runtime.

That’s lexical scope — the variable’s meaning is locked in by the code’s layout.

If Python used dynamic scope, it would check where the function was called from instead — but Python (thankfully) doesn’t. Lisp fans, you may leave your torches at the door. 🔥

🧠 Closures: Functions That Remember

A closure is what happens when an inner function remembers variables from its enclosing scope — even after that outer function has finished running.

Example:

Even though make_counter() is long gone, increment() still remembers count.

It’s like your function has a tiny memory chip inside it — that’s a closure.

Closures are powerful: they enable decorators, maintain state, and are basically the reason Python feels magical sometimes.

🕵️ Inspecting Scopes at Runtime

Okay, time to get sneaky. Python lets you peek under the hood and inspect what’s in your scopes — live.

Using globals() and locals()

You’ve seen these before, but they’re even more fun in the REPL:

Output (abridged):

globals() shows what lives at the module level.locals() reveals what’s alive in your current function or block.

Using the inspect Module

The inspect module takes it even further:

This shows your current frame’s variables and even the parent’s. It’s like a time machine for debugging.

⚠️ Just don’t rely on it in production code — it’s mostly for introspection, debugging, and the occasional “how does this even work?” curiosity binge at 2 a.m.

🧱 Namespaces in Classes and Modules

We’ve talked about function scopes, but what about classes and modules?

Python gives both their own namespaces too!

Class Namespaces

Output:

Here’s what’s happening:

-

The class namespace holds

planetandintro. -

Each instance gets its own

__dict__holdingself.name.

When Python can’t find something in the instance, it checks the class, then the module — it’s a mini-LEGB chain inside your object.

🧩 Module Namespaces

Every .py file is a module, and each module has its own global namespace.

So if you import a module, Python creates a separate namespace for it — preventing name collisions between different files.

That’s why you access names as module.name — you’re dipping into another module’s namespace.

🧘♂️ TL;DR: Advanced Scope Mastery

| Concept | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Lexical Scope | Scope defined by code structure | Inner function uses outer variable |

| Closure | Inner function remembers state | Counters, decorators |

| inspect Module | View frames and locals | Debugging scope |

| Class Namespace | Holds class vars & methods | Hero.planet, self.name |

| Module Namespace | Each file’s global space | utils.value |

Understanding these advanced scoping rules is like learning to see The Matrix — suddenly, everything in Python makes perfect sense. 💡

🧹 Best Practices for Managing Scope and Namespace in Python

Python gives you a lot of freedom — but with great power comes great responsibility.

Without some discipline, your code can quickly turn into spaghetti, with global variables sneaking around like mischievous gremlins.

Here are the best practices to keep your scopes and namespaces neat, tidy, and predictable.

1️⃣ Use Clear and Descriptive Names

Avoid vague names like x, y, or worse — list (don’t shadow built-ins!).

✅ Good: user_count, config_dict, max_score

❌ Bad: a, b, list

Clear names reduce shadowing and make debugging a breeze. Your future self will thank you.

2️⃣ Avoid Unnecessary Global Variables

Global variables are tempting, but they create hidden dependencies.

Instead:

-

Pass variables as function parameters.

-

Return modified values instead of mutating global state.

-

If you must use globals, encapsulate them in a dictionary or class for clarity.

Example:

3️⃣ Keep Functions Small and Pure

A pure function:

-

Depends only on its inputs.

-

Has no side effects (doesn’t touch globals).

Smaller, focused functions are easier to reason about and reduce scope-related headaches.

4️⃣ Use Closures Thoughtfully

Closures are powerful, but overusing them can make code hard to follow.

✅ Good use: maintaining state for decorators or counters

❌ Bad use: nesting multiple layers for simple tasks — readability suffers

5️⃣ Avoid Shadowing Built-ins

As we covered earlier, don’t name variables after Python built-ins like list, dict, max, sum.

Python follows the LEGB rule, so if your local variable shadows a built-in, you’re in for mysterious errors.

6️⃣ Mind Class and Module Namespaces

-

Use instance variables for per-object data.

-

Use class variables for shared data across objects.

-

Access module-level variables via

module.nameinstead of polluting your global scope.

7️⃣ Code Readability and Maintainability Tips

-

Keep the number of nested functions minimal.

-

Document where variables are declared and why globals/nonlocals exist.

-

Use tools like

globals(),locals(), andinspectfor debugging scope issues.

Think of it like decluttering your Python home — fewer surprises, easier to maintain, and more fun to live in. 🏡

💬 TL;DR

-

Name variables clearly.

-

Minimize global variables.

-

Keep functions small, pure, and focused.

-

Use closures wisely.

-

Don’t shadow built-ins.

-

Be mindful of class/module namespaces.

-

Document and debug scope issues proactively.

Follow these practices, and you’ll write Python code that scales, survives, and doesn’t spontaneously explode.

🌍 Real-World Examples and Use Cases: Python Scope in Action

1️⃣ Using Closures for Data Encapsulation

Closures are perfect for keeping state hidden while providing controlled access.

Here, count lives safely in the enclosing namespace — nothing outside can touch it.

Closures = secret lockers for your data. 🔒

SEO keyword: “Python closures example”

2️⃣ Managing Configuration Using Global Variables Safely

Sometimes a small, controlled global variable is reasonable — like application-wide settings.

By using a single global dictionary, you avoid scattering globals everywhere.

SEO keyword: “modify variable scope Python”

3️⃣ Understanding Scope in Decorators

Decorators often rely on closures and scope rules.

wrapper() accesses message from the enclosing function.

This demonstrates LEGB in practice — decorators wouldn’t work without proper scope handling.

SEO keyword: “Python decorators scope”

4️⃣ Namespaces in Large Projects and Modular Code

In big projects, module namespaces keep things organized:

Each module has its own global namespace, preventing collisions between different parts of the project.

Understanding namespaces here is essential to avoid NameError and messy globals.

SEO keyword: “namespace use cases Python”

💡 Quick Takeaways

-

Closures = keep state safe & encapsulated.

-

Global configs = okay if centralized & minimal.

-

Decorators = closures + scope = magic.

-

Modules = namespaces keep big projects sane.

Mastering scope and namespaces isn’t just academic — it’s the difference between a Python script that works once and a Python project that survives years of growth.

🎯 Conclusion: Mastering Python Scope and Namespace

By now, you’ve traveled through the full landscape of Python scope and namespace — from the tiniest local variable to the lofty heights of built-in functions.

Here’s the recap:

-

Namespaces are Python’s internal mapping of names → objects. They exist at four levels: local, enclosing, global, and built-in. Think of them as tidy drawers where Python keeps track of every variable, function, and class.

-

Scope determines where a variable is accessible. Local variables live inside functions, global variables at the module level, and built-ins are always available. Python uses lexical (static) scoping, so a variable’s scope is set by its location in the code, not where it’s called.

-

LEGB Rule — Local → Enclosing → Global → Built-in — is Python’s variable lookup hierarchy. Understanding it explains why some variables disappear mysteriously while others stubbornly shadow your names.

-

Global and Nonlocal Keywords let you intentionally modify variables outside the current local scope. Use them sparingly; they’re like superpowers — great when used wisely, chaotic if abused.

-

Common pitfalls like

UnboundLocalError, variable shadowing, overwriting built-ins, and mutable type confusion happen to everyone. Awareness plus debugging tools likeglobals(),locals(), andinspectcan save your sanity. -

Advanced topics — closures, class and module namespaces, and runtime inspection — elevate your code from working scripts to maintainable, modular Python projects.

-

Best practices: use descriptive names, minimize global variables, write small and pure functions, handle closures carefully, and keep your namespaces organized.

-

Real-world applications: closures for encapsulation, global configs for controlled state, decorators, and modular project design all rely on a deep understanding of scope and namespaces.

💡 Why This Matters

Mastering scope and namespace isn’t just an academic exercise.

It makes your code debuggable, maintainable, and scalable.

It prevents the sneaky bugs that appear only in production.

It empowers you to write Python code that behaves exactly as intended — no more “why isn’t my variable defined?” moments.

🏁 Next Steps

-

Experiment with closures and nested functions.

-

Play with

globalandnonlocalto see how LEGB works in real scenarios. -

Inspect scopes using

globals(),locals(), andinspect. -

Explore related Python concepts: decorators, context managers, and function factories.

Once you internalize these rules, Python’s variable world stops being mysterious and starts being predictable — and that’s a superpower worth having. ⚡

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=60BhDMIm5vk&t=6s