Introduction: Renting Memory Like a Pro

Ah, memory management in C. The land where you manually juggle every byte, and one wrong move sends your program into the abyss of segmentation faults. But fear not! You’re not alone — every C programmer, from nervous newbie to grizzled systems dev, has at some point yelled at a malloc() call that returned NULL.

So, why does memory management matter? Think of it like renting instead of buying. When you allocate memory dynamically, you’re temporarily renting a space on the heap — like booking a hotel room on the fly. You don’t want to trash the place or leave your stuff behind (hello, memory leaks). Stack memory is like crashing on your friend’s couch — temporary, and automatically cleaned up. But the heap? You’ve got to clean up after yourself, or someone’s going to have a bad time.

In this memory-packed journey, we’ll explore:

- The difference between the stack and heap

- How to use

malloc(),calloc(),realloc()like a wizard - Why

free()is your best friend (and also your potential enemy) - How to avoid nasty bugs like memory leaks and use-after-free errors

- Pro tips, tools, real-world analogies, and even some interview magic

Whether you’re a curious student, an embedded enthusiast, or someone who’s accidentally freed the stack (don’t do that), this guide will help you master memory like a pro.

Let’s dive deep into the mysterious internals of malloc() and friends, and emerge victorious, pointer in hand.

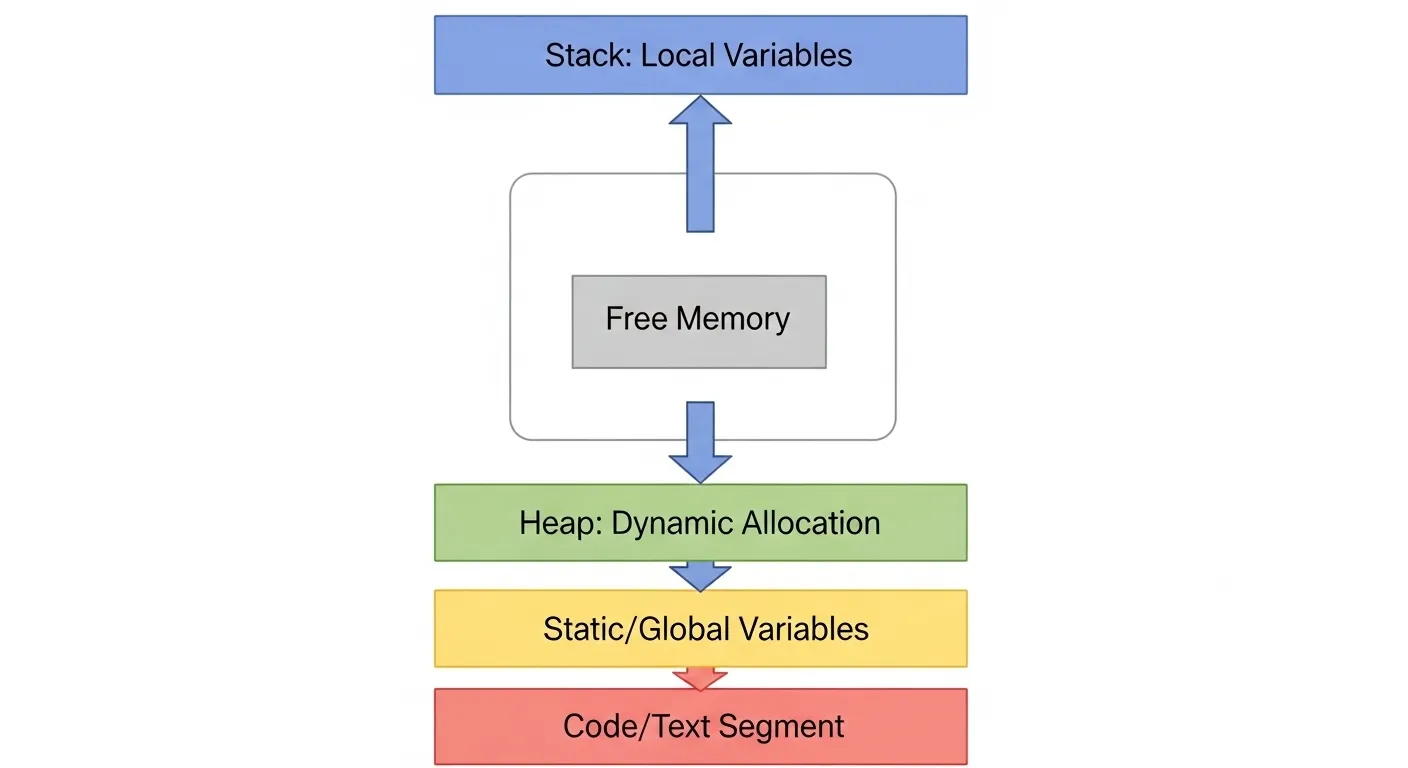

Section 1: Understanding Memory in C – Stack vs Heap

Let’s start at the root of all memory-related confusion: stack vs heap. These are the two main types of memory in C, and they behave very differently.

Stack Memory 🥞

The stack is like your call history — it’s managed automatically and follows a Last-In-First-Out (LIFO) structure. When you declare a local variable in a function, it gets a spot on the stack.

void greet() {

char name[10]; // This lives on the stack

}Once the function ends, that memory is reclaimed. No free() needed.

Heap Memory 🧠

The heap is where you go when you want to allocate memory manually. Think of it as your own private storage space — more flexible, but also your responsibility to maintain.

char* name = malloc(10); // This lives on the heapNow you are responsible for freeing it when you’re done.

Diagram: Stack vs Heap

Memory Layout:

+-----------------------+

| Stack ↑ |

| Local Variables |

+-----------------------+

| Heap ↓ |

| Dynamically Alloc'd |

+-----------------------+When to Use What?

- Stack: For small, short-lived variables scoped to functions.

- Heap: For large, dynamic data structures (arrays, structs, buffers) or when lifetime extends beyond function scope.

Common Rookie Mistake ⚠️

Using stack-allocated memory after the function returns:

char* getName() {

char name[10];

return name; // BAD! Memory gone after return

}This leads to undefined behavior. Use heap memory for data that must outlive its function.

Section 2: malloc() – The OG Allocator

If stack memory is automatic, malloc() is your manual gear shift. It’s the Original Gangster of memory allocation.

Syntax:

void* malloc(size_t size);It allocates size bytes on the heap and returns a pointer to the first byte. If it fails, it returns NULL.

Example:

int* scores = (int*) malloc(5 * sizeof(int));Technically, typecasting is not required in C (only in C++), but many developers do it out of habit or for clarity.

Always Check for NULL ✅

if (scores == NULL) {

// Handle allocation failure

}Pitfall #1: Uninitialized Memory

malloc() gives you raw memory. That means garbage data:

int* data = malloc(3 * sizeof(int));

printf("%d\n", data[0]); // Could be anything!Pitfall #2: Miscalculating Size

char* name = malloc(10); // OK for 9 chars + null terminator

char* wrong = malloc(10 * sizeof(char*)); // Way too bigAnalogy:

Using malloc() is like renting an apartment without checking if it’s clean or even has walls. You have space, but no guarantees.

Section 3: calloc() – malloc’s More Careful Cousin

If malloc() is your fun but chaotic friend who hands you a pile of memory and says, “Good luck!”, then calloc() is the neat freak cousin who hands you clean, zeroed-out memory with a smile and a checklist.

Syntax:

Instead of just specifying a total byte count like in malloc(), you provide two arguments:

-

num: the number of elements -

size: the size of each element

It returns a pointer to a block of memory large enough to hold num * size bytes, all initialized to zero.

Example:

The Key Difference: Zero-Initialization 🧼

While malloc() just grabs raw memory, calloc() makes sure the entire block is wiped clean — every byte is set to 0. This is especially useful when:

-

You’re working with arrays that need a known starting value.

-

You’re initializing structs where zeroed values make sense.

-

You don’t want to manually

memset()after allocating.

Real-World Analogy:

Think of calloc() as renting a furnished, freshly cleaned apartment — the fridge is empty, the counters are wiped, and the sheets are washed. Meanwhile, malloc() is like getting an apartment where the last tenant may have left socks in the closet. You just don’t know.

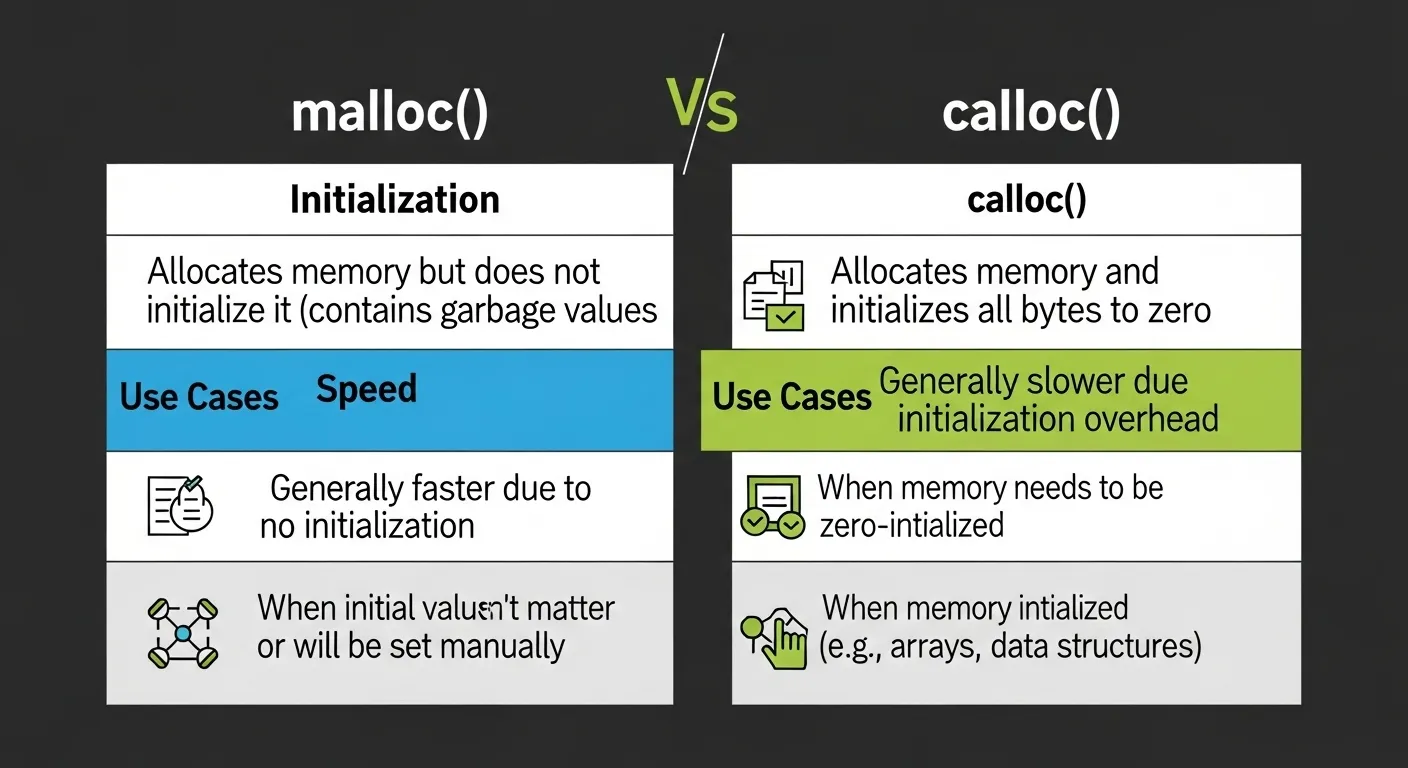

malloc() vs calloc(): When to Use What?

| Feature | malloc() |

calloc() |

|---|---|---|

| Initialization | ❌ Garbage data | ✅ Zeroed-out memory |

| Performance | ⚡ Slightly faster | 🐌 Slightly slower (but safer) |

| Use Case | Manual setup | Structs, arrays, safe defaults |

Common Use Case: Struct Arrays

This makes calloc() a great choice when your program relies on default (zero) values for correctness.

Performance Consideration:

Yes, calloc() is technically slower because of the zeroing step. But modern operating systems often optimize it using techniques like copy-on-write and lazy allocation, so unless you’re in an ultra performance-critical loop (like in an embedded system), the performance difference is often negligible.

Common Gotcha:

Some folks think calloc() magically prevents all bugs because it initializes to zero. Sadly, no. It won’t protect you from buffer overflows, logic bugs, or forgetting to free() later. It just helps eliminate one common source of undefined behavior — using uninitialized memory.

Section 4: realloc() – Resizing Memory on the Fly

You’ve malloc()’d some memory, written some brilliant code, and now — uh oh — your array isn’t big enough. Enter realloc(), the resizing wizard of C. It lets you adjust the size of previously allocated memory, without starting from scratch. Magic? Almost.

Syntax:

-

ptr: the pointer to memory previously allocated viamalloc(),calloc(), or even anotherrealloc() -

new_size: the new size in bytes

Returns a pointer to the new memory block, which may or may not be at the same address.

Example: Growing an Array

Now you can use bigger[0] through bigger[5]. Note: if the system can’t expand the block in place, it allocates new memory, copies the old content, and frees the old block automatically.

realloc() Can Move Your Data 📦

Just like upgrading your apartment — you might stay in the same building, or you might have to move across town. That’s what realloc() does: it may relocate your memory.

So what’s the catch?

Pitfall #1: Losing Your Pointer 😱

But what if realloc() fails and returns NULL? You’ve now lost the original pointer and leaked memory.

Safer pattern:

Pitfall #2: NULL as the First Argument

Calling realloc(NULL, size) is the same as malloc(size). This means realloc() can double as an allocator. Handy, but potentially confusing.

Pitfall #3: Downsizing Woes

Shrinking memory may leave old data behind — but if you access beyond the new boundary, you’re in undefined behavior land. Don’t go there. Seriously.

Real-World Analogy: Apartment Upgrade

Realloc is like asking your landlord for a bigger place. If they can expand your current apartment, great! If not, you move — and the landlord helps you move your stuff. But if the landlord says “Nope, we’re full,” and you already packed your bags and gave up your lease… well, now you’re homeless. That’s the realloc failure trap.

Use-Case: Dynamic Input Buffers

This pattern — doubling buffer size — is common in real-world C input handling (e.g., reading unknown-length strings).

Section 5: The Art of free() – Cleaning Up Like a Pro

Let’s get one thing straight: if you malloc(), calloc(), or realloc(), you must eventually free(). Otherwise, you’re leaving your memory rented and unpaid — and in C, there’s no landlord to chase you. Instead, you just silently cause memory leaks, and your program becomes a digital hoarder.

Syntax:

Simple, right? But like any deceptively simple tool (looking at you, chainsaws), free() can be dangerous if misused.

Why It’s Essential: Avoiding Memory Leaks 💧

When you allocate memory on the heap, it stays allocated until:

-

You explicitly

free()it -

The program exits (and even then, OS cleanup isn’t guaranteed — especially in embedded systems)

If you don’t free() memory you’ve allocated, that memory is never returned to the system. Over time, this is like stuffing every room you’ve ever rented with junk and walking away. It adds up.

Example:

Common Mistake #1: Double Free ❌❌

Double freeing is like trying to hand back an apartment key — twice. The second time, the system says, “Dude, this place doesn’t belong to you anymore,” and chaos ensues.

Common Mistake #2: Freeing Stack Memory

Stack memory is automatically cleaned up. Trying to free() it is like trying to evict someone from your own couch.

Common Mistake #3: Use After Free

Accessing memory after free() is like trying to use a phone number after someone moved. It might work… but it probably won’t, and someone else might be living there now.

How to Stay Safe 🛡️

-

After calling

free(ptr), setptr = NULL. That way, accidental second frees or use-after-free bugs will be caught early.

Pro Tip: Free in Reverse Order

If you allocate multiple blocks, free them in the reverse order you allocated. Think of it as stacking dishes — take the last one off first.

Tools That Help:

-

Valgrind: Detects memory leaks, use-after-free, and other nasties.

-

AddressSanitizer (GCC/Clang): Catches out-of-bounds and freed-memory access.

-

Static Analyzers: Many IDEs and tools can catch misuse before runtime.

Real-World Analogy:

Imagine renting a storage unit, leaving a mattress inside, and walking away. Every month, you still get charged. Now multiply that by 20 storage units — that’s what a memory leak looks like in production.

Section 6: Memory Management Best Practices

Ah, memory in C — a thing of power and peril. It’s like owning a chainsaw: awesome when used right, horrifying when misused. So, here are your golden commandments for writing clean, leak-free, crash-resistant C code.

🧪 1. Always Check malloc/calloc Return Values

If you skip this, you’re gambling with your program’s life.

Never assume memory allocation will always succeed — especially in low-RAM environments or when your program scales up.

🧹 2. Always Free What You Malloc (But Only Once!)

If you allocate it, you deallocate it. If you forget, it leaks. If you do it twice, it explodes.

Bad:

Better:

🧭 3. Keep Ownership Clear

Who owns the pointer? Is it passed between functions? Shared globally? These questions matter.

Use comments and good function naming to clarify ownership:

🔁 4. Pair Allocations and Deallocations Logically

Allocate and deallocate in the same conceptual place. For example:

This prevents memory leaks and makes your code easier to audit. Bonus: tools like Valgrind love you for this.

⏳ 5. Know the Memory Lifecycle

Ask yourself:

-

Does this memory live just for a function?

-

Is it passed around to other modules?

-

Does it last the life of the program?

This tells you whether to use stack or heap, and where to free the memory.

💡 Bonus: Use Wrapper Functions

You can create your own safe_malloc() function to enforce checks: