Introduction

“If it looks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck… it’s probably a duck.”

You’ve probably heard this phrase tossed around in programming circles, often by someone who just wrote Python code that somehow works without any explicit type declarations — and they’re beaming with pride (or mild confusion). Welcome to the world of Duck Typing in Python, where the motto is basically: Don’t ask what it is — just see if it can quack.

In more technical terms, duck typing is Python’s way of saying, “I don’t care what type you say you are; I care about what you can do.”

If an object behaves like the thing we need — say, it has the method or attribute we’re about to call — then Python’s happy to roll with it. No permission slips, no type declarations, no long forms in triplicate.

This approach is part of what makes Python so refreshingly human to work with. You write code that reads like thought, not bureaucracy.

duck typing is Python’s way of saying, “I don’t care what type you say you are; I care about what you can do.”

🧠 What Is Duck Typing (In Simple English)?

Duck typing is a style of dynamic typing — meaning Python decides an object’s type at runtime, not ahead of time.

Let’s say you have a function that calls quack() on whatever you pass it. In Python, as long as the object you pass actually has a .quack() method, everything’s fine. You don’t need to declare a type, subclass a specific base, or go through any formalities.

It’s like hiring someone because they can do the job, not because they have a certain degree.

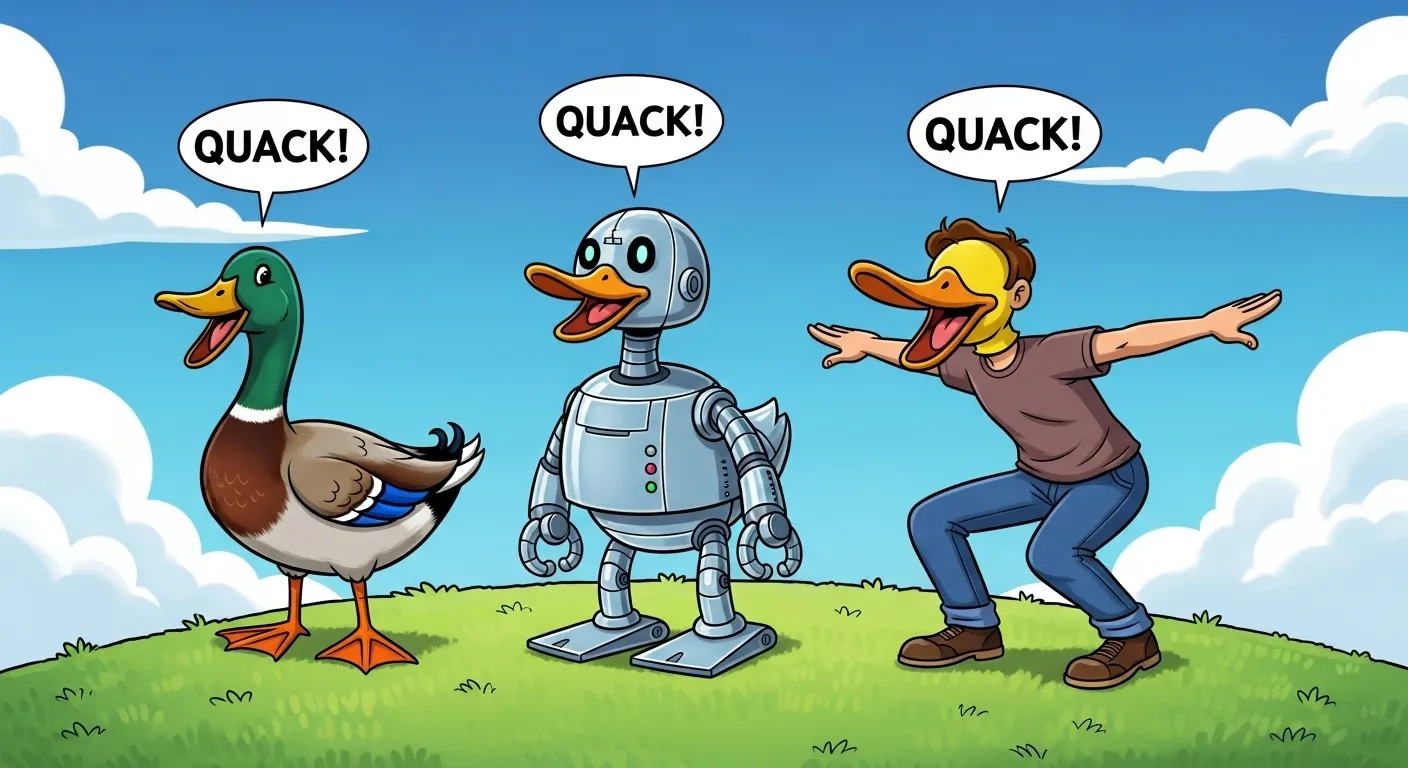

Here’s a quick mental image:

-

Java or C++: “Please fill out this form, show your ID, and prove you’re a Duck before we let you quack.”

-

Python: “Just quack already.”

That’s the magic of duck typing — flexibility first, paperwork later (or never).

⚖️ Duck Typing vs Static Typing

In statically typed languages like Java or C++, the compiler wants to know the type of everything before it even lets your code run. If you try to pass a Person to a function expecting a Duck, it’ll throw a fit before you can even hit “Run.”

Python, being dynamically typed, says:

“I’ll trust you. If it quacks fine at runtime, we’re good. If it doesn’t… well, you’ll find out soon enough.”

That’s the trade-off — freedom and speed versus safety and predictability. You can move fast and build prototypes quickly, but if something doesn’t quack when you expected it to, you’ll hear about it during execution.

🧩 Why Duck Typing Matters

Duck typing is more than a quirk — it’s philosophically Pythonic.

It embodies Python’s “consenting adults” approach: programmers are trusted to use objects responsibly without excessive guardrails.

This philosophy leads to:

-

Cleaner, more readable code (no type boilerplate everywhere).

-

Easier polymorphism — different objects can share behavior naturally.

-

Rapid prototyping — build now, refine later.

It’s one of the reasons Python feels so natural. You can focus on what the code does, not on what every variable claims to be.

🔍 What You’ll Learn

In this guide, we’ll wade through the duck pond of Python typing — from theory to real-world examples — and come out knowing:

-

What duck typing really means (and where the term came from).

-

How it compares to static typing (with code examples).

-

Its relationship with polymorphism, interfaces, and type hints.

-

Real-world use cases in frameworks like Django and Pandas.

-

Best practices, pitfalls, and misconceptions.

By the end, you’ll not only understand why duck typing is such a big deal in Python — you’ll probably start writing more Pythonic code without even realizing it.

So, grab your rubber duck (the debugging kind), and let’s dive in. 🦆

II. Understanding the Concept of Duck Typing

🐣 Where “Duck Typing” Comes From

Let’s start with the origin story — no, not from a fairy-tale swamp, but from an old philosophical saying known as the “Duck Test”:

“If it looks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, it probably is a duck.”

This idea slipped into programming as a metaphor for behavior-based identification. Instead of caring about what something is (its class or type), we care about what it can do.

So, when Pythonistas say “duck typing,” they mean: if an object acts like the type we need — by implementing the expected methods or attributes — then that’s good enough.

No ID checks. No type interrogations. Just vibes and valid method calls.

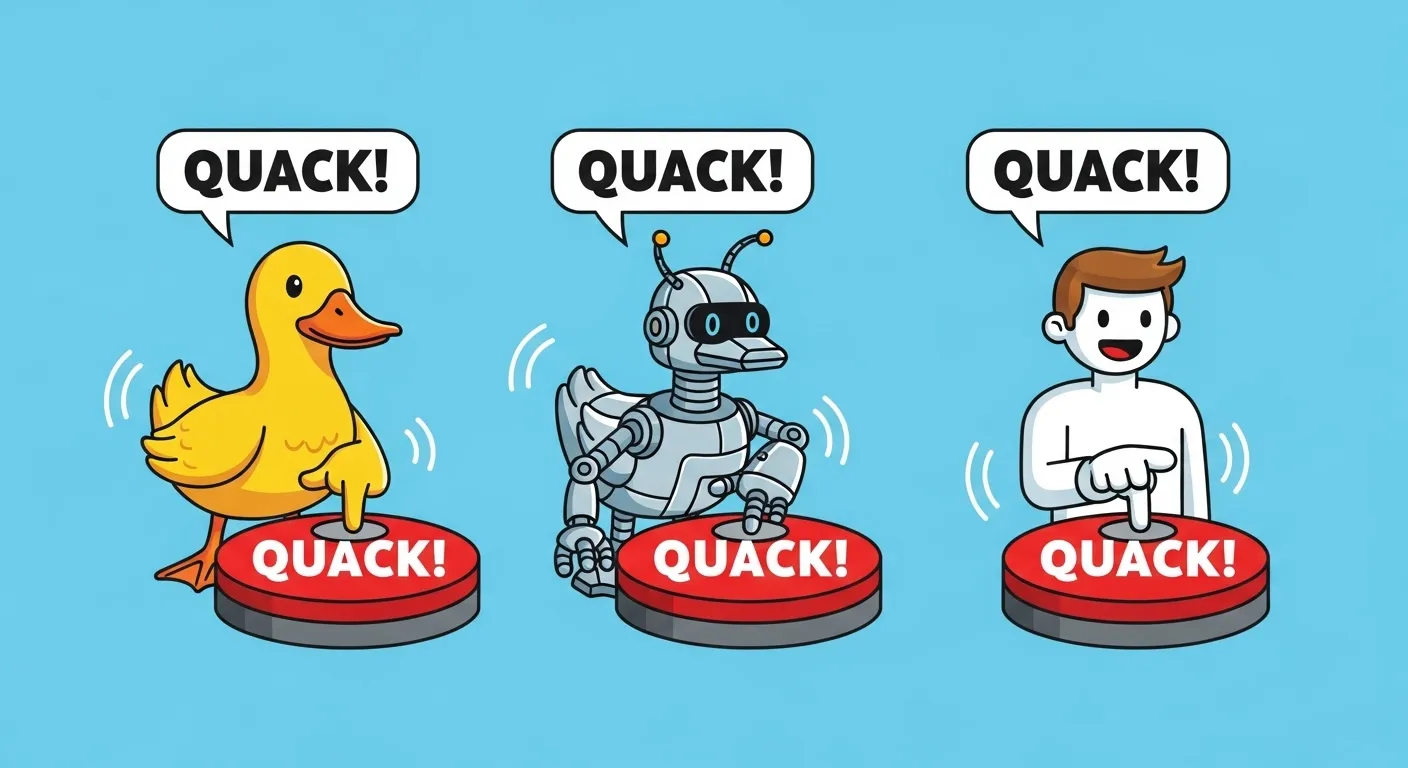

💡 The Core Idea: Behavior > Type

In traditional statically typed languages, types are like strict job titles. You must declare exactly what you are — int, string, Duck, etc. — and the compiler enforces those boundaries with the energy of a grumpy librarian.

Python, on the other hand, is like that cool manager who says, “I don’t care what’s on your resume — can you do the job?”

Duck typing shifts the focus from identity to capability.

In other words:

“Don’t tell me what you are. Show me what you can do.”

If an object can perform the required action — say, it can .quack() — Python doesn’t need it to be of class Duck. It could be a Person, a Robot, or a RubberDuckSimulator9000. As long as it quacks on demand, Python’s happy.

⚙️ Python’s Type System: The Dynamic Touch

Under the hood, Python uses dynamic typing.

This means variables don’t have fixed types — they’re just labels that can point to any object at runtime.

In Python’s world, x doesn’t care about sticking to one type. It’s like a free-spirited variable just trying to live its best polymorphic life.

When you pass an object to a function, Python doesn’t check its declared type. It only checks at runtime whether the object has the required methods or properties. If it doesn’t — boom — you’ll get an AttributeError.

That’s the price of freedom: flexibility now, accountability later.

☕ Everyday Analogy

Imagine you run a coffee shop. You don’t care who delivers your coffee beans — FedEx, UPS, or a local courier — as long as they:

-

Show up on time, and

-

Drop off the beans.

You don’t demand they inherit from a DeliveryService base class. You just expect them to have a .deliver() method.

That’s duck typing in a nutshell — no red tape, just results.

🐤 A Simple Example

Here’s a classic Python duck typing example:

Output:

🔍 What Just Happened?

When we called make_it_quack(Duck()), the Duck instance’s .quack() method ran — no surprises there.

But when we called make_it_quack(Person()), Python didn’t complain, even though Person isn’t a subclass of Duck. It simply checked:

“Does this object have a

.quack()method?”

It did — so Python let it pass.

That’s duck typing in action:

-

No inheritance.

-

No interfaces.

-

No static type checks.

-

Just behavior that walks and talks like a duck.

🧩 The Beauty of Simplicity

This concept might sound chaotic to developers coming from statically typed backgrounds. But it’s incredibly elegant once you embrace it.

Duck typing makes code more flexible, more reusable, and easier to extend. You can write functions that operate on any object that fulfills a certain contract — without explicitly tying them to a base class or interface.

That’s why frameworks like Django, Flask, and Pandas lean heavily on this principle. They don’t require rigid inheritance hierarchies — they just need your objects to behave right.

⚠️ But Wait, There’s a Catch

All that freedom comes with one caveat: you might not discover a missing .quack() until runtime.

If you accidentally pass an object without the right method, Python won’t stop you at compile time. Instead, it’ll raise an AttributeError mid-quack.

That’s where tools like type hints and static analysis (we’ll get there later!) come in — they let you enjoy duck typing’s flexibility while catching mistakes early.

🦆 In Short

Duck typing is Python’s way of saying:

“If it quacks like a duck, let it quack.”

It’s a powerful, flexible, and deeply Pythonic approach that focuses on what objects can do, not what they claim to be.

And once you start thinking this way, your code becomes less rigid, more expressive, and a lot more fun.

III. Duck Typing vs Static Typing

⚔️ The Great Typing Showdown

If programming languages were high school archetypes, Java would be the serious, rule-abiding student with a color-coded planner, and Python would be the chill genius who gets A’s without showing their work.

The difference?

Java insists on knowing exactly what every variable is before class starts — Python just trusts it’ll figure it out when it needs to.

That’s the essence of static vs dynamic typing, and duck typing is Python’s cheeky twist on the latter.

🧱 Static Typing in a Nutshell

Static typing means every variable’s type is known — and checked — before your program runs.

Languages like Java, C++, or Rust use this approach. When you compile your code, the compiler checks if everything matches perfectly: types, assignments, method calls — the whole nine yards.

If you make a mismatch, the compiler throws a tantrum immediately:

class Person {

void quack() {

System.out.println(“I’m pretending to be a duck!”);

}

}

public class Main {

static void makeItQuack(Duck d) {

d.quack();

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

makeItQuack(new Duck()); // ✅ Works fine

makeItQuack(new Person()); // ❌ Compile-time error!

}

}

Result:

Java refuses to even run the program because Person isn’t a Duck.

Static typing is like a strict bouncer — no entry unless your ID matches exactly.

🪶 Dynamic Typing: Python’s Freestyle

Python, being dynamically typed, doesn’t check types at compile time (because there’s no compilation phase like Java’s). Instead, it checks at runtime — when your code actually runs.

class Person:

def quack(self):

print(“I’m pretending to be a duck!”)

def make_it_quack(thing):

thing.quack()

make_it_quack(Duck()) # ✅ Works

make_it_quack(Person()) # ✅ Also works!

Output:

Python doesn’t care whether the object is a Duck or a Person.

As long as it has a .quack() method, it’s all good.

But — and here’s the trade-off — if you pass something that can’t quack:

You’ll get this runtime slap:

That’s duck typing: flexible, friendly, and occasionally unforgiving.

🧾 Side-by-Side Comparison

| Feature | Static Typing (Java) | Duck Typing (Python) |

|---|---|---|

| Type Checking | Compile-time | Runtime |

| Flexibility | Rigid | Very flexible |

| Error Detection | Early (before running) | Late (while running) |

| Speed of Development | Slower (more setup) | Faster (less boilerplate) |

| Safety | Strong — fewer runtime surprises | Weaker — runtime errors possible |

| Code Readability | Verbose but explicit | Concise and expressive |

💪 Pros of Duck Typing

-

Simplicity – No type declarations cluttering your code.

-

Flexibility – Works with any object that behaves correctly.

-

Rapid Prototyping – Great for quick development and experimentation.

-

Readable Code – Pythonic elegance at its finest: code that looks like pseudocode.

You can focus on behavior and intent, not bureaucracy.

😬 Cons of Duck Typing

-

Runtime Errors – You might not catch mistakes until execution.

-

No Explicit Contracts – Harder to know what type a function expects.

-

Debugging Challenges – When something breaks, it may not be immediately clear why.

-

Tooling Limitations – Without type hints, IDEs can’t help much with autocomplete or static checks.

Duck typing gives you the freedom to move fast — but also the freedom to trip on your own shoelaces if you’re not careful.

⚖️ Finding the Balance

Python’s philosophy doesn’t demand you pick a side.

You can enjoy duck typing’s flexibility and use type hints to catch potential issues early (we’ll explore that in Section VI).

That’s what makes modern Python so powerful — it lets you code like an artist and debug like an engineer.

🦆 TL;DR

-

Static Typing: “Tell me who you are before you speak.”

-

Duck Typing: “Just quack, and we’ll see.”

Python’s dynamic typing lets you focus on behavior — but remember: with great flexibility comes great responsibility (and the occasional AttributeError).

IV. Polymorphism and Duck Typing

🧬 So… What Exactly Is Polymorphism?

If you’ve ever called len() on a string, a list, or even a tuple — and it just worked — congratulations! You’ve already experienced polymorphism in Python.

Polymorphism, from the Greek for “many forms,” means different objects can respond to the same function or method call in their own unique way.

In simple terms:

You can use the same interface, and Python figures out what to do based on the object you pass.

Here’s a super simple example:

Each of these types implements its own __len__ method — and yet, len() works seamlessly across all of them. That’s polymorphism: same operation, different behavior.

🦆 Duck Typing: The “Polymorphism Without Paperwork” Approach

In many languages (like Java or C++), polymorphism requires inheritance — classes must share a common parent or implement the same interface.

Python takes a simpler, more Zen-like approach:

“If it behaves like it should, that’s good enough.”

That’s where duck typing comes in.

Duck typing is essentially informal polymorphism — you don’t need to define a shared base class or interface. As long as the object provides the required behavior, Python treats it as compatible.

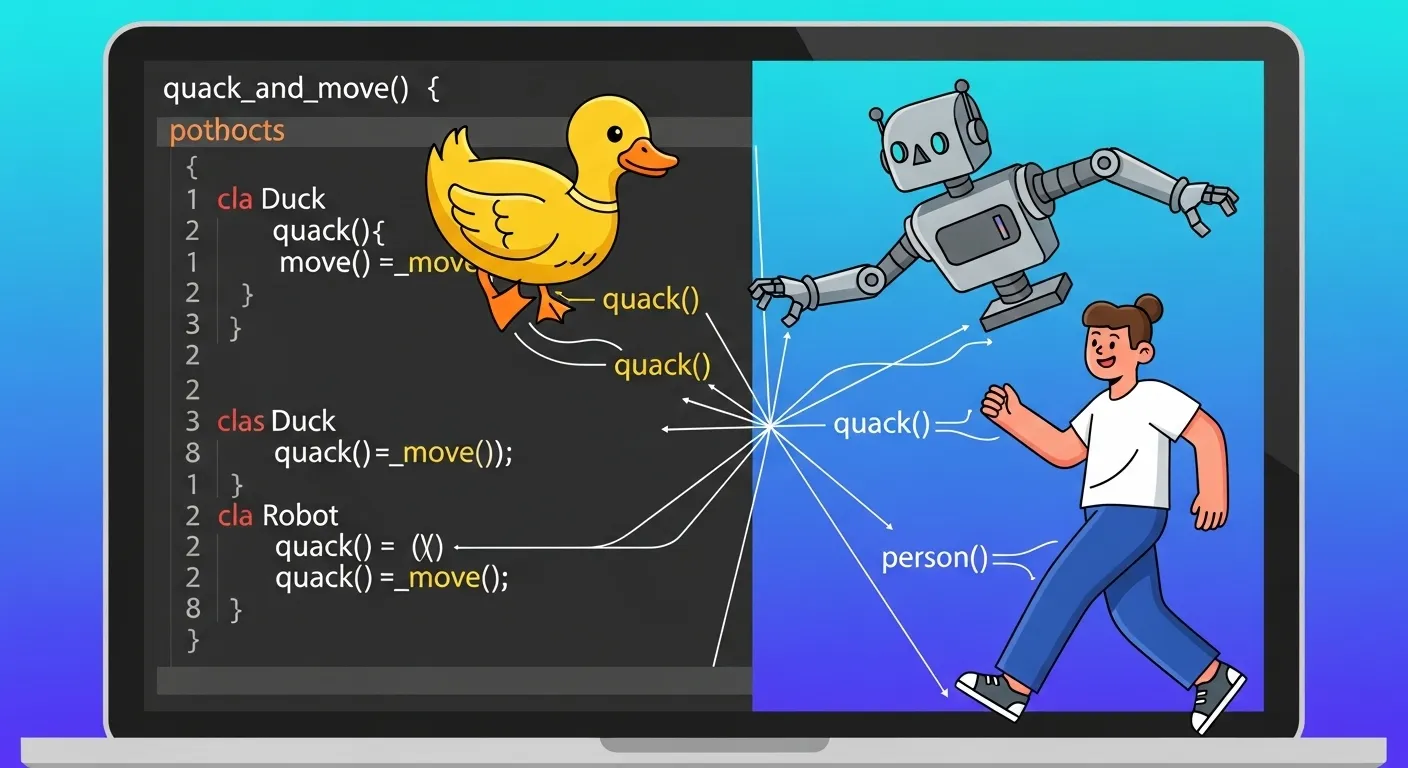

Let’s illustrate that with a classic duck-themed demo:

class RobotDuck:

def quack(self):

print(“Mechanical quack activated.”)

class Person:

def quack(self):

print(“I’m pretending to be a duck!”)

def make_it_quack(thing):

thing.quack()

for thing in [Duck(), RobotDuck(), Person()]:

make_it_quack(thing)

Output:

None of these classes inherit from each other.

No DuckInterface. No boilerplate. Just three unrelated classes that all happen to implement .quack().

Yet, Python happily calls quack() on all of them.

That’s polymorphism powered by duck typing — same call, many forms, no red tape.

🧩 Duck Typing vs Traditional Polymorphism

Let’s put it this way:

| Concept | Traditional Polymorphism (Java/C++) | Duck Typing (Python) |

|---|---|---|

| Requires Inheritance? | Yes | No |

| Type Checking | Compile-time | Runtime |

| Focus | Shared structure (base class/interface) | Shared behavior (methods/attributes) |

| Flexibility | Limited | Very high |

| Example | class Dog extends Animal |

Any object with .bark() |

So, when people say “Duck typing is polymorphism in Python,” they’re right — but with a twist.

Duck typing is Python’s looser, behavior-first version of polymorphism.

🧠 Why It Matters

This flexible polymorphism allows you to:

-

Write generic, reusable code that works with many object types.

-

Build APIs and libraries that are easy to extend.

-

Avoid deep, tangled inheritance hierarchies.

It’s one of the reasons why Python feels so natural. You don’t need to over-engineer — you just focus on what matters: what the object can do.

⚠️ Quick Reality Check

While duck typing makes polymorphism effortless, it also shifts responsibility to you.

If you call quack() on an object that can’t quack, Python won’t warn you until runtime.

That’s why experienced Python devs often combine duck typing with:

-

Type hints (

typing.Protocol) -

EAFP error handling (

try/except) -

Testing to verify expected behavior

🦢 In Short

-

Polymorphism = Many forms, same interface.

-

Duck Typing = Python’s chill version of polymorphism — no formal inheritance required.

-

Together, they make Python code elegant, expressive, and adaptable.

Duck typing is polymorphism’s laid-back cousin — doesn’t wear a suit, but still gets the job done. 🦆

V. Practical Examples of Duck Typing in Python

🧰 Duck Typing in the Wild

Up until now, we’ve talked about duck typing in theory — fun analogies, quacking classes, and Python philosophy. But where does it actually show up in real-world Python code?

Spoiler: everywhere.

From file handling and database design to libraries like Django, Flask, and Pandas, duck typing silently powers Python’s flexibility. Let’s look at some practical (and slightly cheeky) examples.

🦆 Example 1: Custom Objects That Mimic Built-in Behavior

You can make your own objects behave like built-ins by implementing the same methods.

For instance, let’s say we want an object that acts like a list — even though it’s not literally one.

def append(self, item):

print(f”Adding {item} to the list.”)

self._items.append(item)

def __len__(self):

return len(self._items)

def __getitem__(self, index):

return self._items[index]

my_ducklist = QuackList()

my_ducklist.append(“Python”)

my_ducklist.append(“Rocks!”)

print(len(my_ducklist)) # 2

print(my_ducklist[0]) # “Python”

Even though QuackList isn’t a subclass of list, it behaves like one.

That’s duck typing — our class “looks and quacks” like a list.

You could pass this object to any function expecting a list-like object, and it’ll likely work perfectly.

This technique is everywhere in Python — it’s what makes user-defined types feel seamless in the ecosystem.

📄 Example 2: File-like Objects (The Unsung Heroes)

Duck typing is the reason you can write this:

…and then seamlessly swap f for something entirely different — as long as it has .read() and .write() methods.

For example:

StringIO isn’t a file at all — it’s an in-memory object that acts like one.

You can pass it to functions expecting a “file-like object,” and Python doesn’t care that it’s not on disk.

That’s interface design powered by duck typing: any object that behaves like a file is treated as a file.

This concept underpins countless Python APIs — from logging handlers to web frameworks like Flask that deal with streams and buffers.

🐍 Example 3: Custom Iterables (Making Your Object Loop-Friendly)

Ever wondered how your for loops work on anything iterable?

That’s duck typing again!

As long as an object implements __iter__() and __next__(), it’s iterable — no need to inherit from Iterable.

def __iter__(self):

return self

def __next__(self):

if self.current <= 0:

raise StopIteration

self.current -= 1

return self.current + 1

for num in Countdown(3):

print(num)

Output:

Boom — your own iterable, no base classes needed.

That’s duck typing making iteration feel like magic.

💾 Example 4: Database API Design

Let’s say you’re building a data access layer that supports multiple backends — PostgreSQL, SQLite, or maybe a NoSQL store.

You can design your code to use duck typing so it doesn’t care which backend is active — as long as it provides the same methods (connect(), query(), close()).

class PostgresBackend:

def connect(self): print(“Connecting to Postgres…”)

def query(self, q): print(f”Postgres executing: {q}“)

def close(self): print(“Closing Postgres connection.”)

def run_query(db):

db.connect()

db.query(“SELECT * FROM users”)

db.close()

# Works with either backend:

run_query(SQLiteBackend())

run_query(PostgresBackend())

No inheritance. No abstract base classes. Just duck typing.

This pattern — behavioral compatibility — keeps your code modular and extensible.

⚡ The Real Benefit: Flexible, Maintainable Code

Duck typing lets you design systems around capabilities instead of rigid hierarchies.

You can add new types, mock objects for testing, or swap implementations without refactoring tons of code.

That’s why major Python frameworks embrace it:

-

Flask treats anything with a

.route()decorator or.run()method as a valid app. -

Django ORM uses model-like behavior without enforcing a deep inheritance structure.

-

Pandas DataFrames mimic NumPy arrays to play nicely with mathematical functions.

All thanks to duck typing — the invisible glue of Python’s ecosystem.

💥 Common Gotchas (and How to Avoid Them)

Duck typing’s flexibility can backfire if you’re not careful:

-

Runtime Surprises

If you assume an object has a method it doesn’t, you’ll get anAttributeErrormid-run. -

Silent Failures

If you override built-in methods incorrectly (__iter__,__len__, etc.), your code might behave unexpectedly. -

Debugging Nightmares

When everything’s dynamic, tracing the source of a bug can feel like playing “Guess the Object.”

👉 The fix?

Use type hints, static analysis tools (like mypy), and EAFP (try/except) patterns — we’ll cover those soon.

🧩 Performance and Maintainability

Duck typing itself doesn’t slow Python down — but misuse can.

If you’re constantly doing runtime checks or calling missing attributes, you’ll feel it.

The trick is balance:

-

Use duck typing to stay flexible.

-

Combine it with explicit testing and documentation to stay sane.

🦆 In Summary

Duck typing isn’t just a cute metaphor — it’s the foundation of Python’s design philosophy.

It gives you:

✅ Flexibility to write reusable, elegant code.

✅ Freedom to design intuitive interfaces.

✅ Simplicity to prototype fast — and evolve later.

But like any power tool, it’s best used with safety goggles and a few try/except blocks.

VI. Type Hinting and Duck Typing

🧠 When Dynamic Meets Static: The Best of Both Worlds

Duck typing gives Python its trademark flexibility — code that just works if the object behaves correctly.

But flexibility can sometimes lead to chaos, especially in big projects where you have a lot of quacking going on and no one remembers which object was supposed to quack, squeak, or sing opera.

Enter type hints — Python’s friendly way of saying:

“I’ll still let you quack freely, but maybe wear a name tag so I know who’s who.”

🪶 A Quick Refresher: Type Hints

Introduced in PEP 484, type hints let you annotate your code with expected types — without making Python suddenly static.

They don’t change runtime behavior. Instead, they help developers, IDEs, and linters catch potential issues before they explode.

For example:

This runs fine, but doesn’t tell tools much. You can’t express “anything that can quack” — or can you?

🦆 Enter typing.Protocol: The Duck-Friendly Way to Hint

Starting with Python 3.8, we got Protocol in the typing module (formalized in PEP 544).

It’s basically an official nod to duck typing — a way to express “this thing should act like something,” not “this thing is something.”

Here’s how it works:

Now, any class that implements a .quack() method automatically qualifies as a Quackable.

No inheritance.

No subclassing.

Just pure, behavior-based compatibility.

Example:

class Person:

def quack(self): print(“I’m pretending to be a duck!”)

make_it_quack(Duck()) # ✅ Works

make_it_quack(Person()) # ✅ Works

Even though neither Duck nor Person inherits from Quackable, static type checkers like mypy or pyright will recognize them as valid types — because they both have .quack().

That’s duck typing with static validation — a beautiful union of chaos and control.

🧩 Why Type Hints Don’t Break Duck Typing

A common misconception is that adding type hints makes Python “static.” Nope.

Duck typing still rules the runtime. Type hints just make your intent clearer.

When you add a Protocol or type hint:

-

You’re not locking types — you’re documenting behavior.

-

Python won’t enforce it at runtime.

-

Static analysis tools will help you catch mismatched calls early.

So your code still runs dynamically, but now you can sleep better knowing that if you accidentally call .quack() on a rock, your IDE will at least warn you first.

🧰 Static Analysis Tools: The Safety Net

Tools like mypy, pyright, and PyCharm’s built-in checker analyze your code based on type hints.

They won’t stop execution, but they’ll flag potential type errors before runtime.

For instance, mypy will yell at you if you pass an object without .quack() to a function expecting a Quackable.

And that’s a good thing — you catch errors before your ducks hit production.

⚖️ Balancing Flexibility and Safety

The magic of Python today is you don’t have to choose between:

-

Static safety (Java-style rigidity), and

-

Dynamic freedom (pure duck typing).

You can blend them:

-

Use duck typing for flexibility.

-

Add type hints and Protocols for clarity and confidence.

That’s modern, mature Python development — flexible, readable, and robust.

🦆 In Summary

Type hints don’t cage the duck — they just give it a GPS tracker.

-

Duck typing keeps Python dynamic and expressive.

-

Type hints and

Protocolmake it predictable and maintainable. -

Together, they let you write cleaner, safer, more professional Python.

So yes, you can have your quack and type-check it too.

VII. Duck Typing vs Interfaces & Abstract Classes

🥸 “Do I look like an interface to you?”

If you’ve come from a background in Java, C#, or other statically typed languages, you’re probably used to interfaces — those strict contracts that say:

“If you want to be part of this club, you must implement these methods exactly.”

Python, being the cheeky rebel that it is, says:

“Nah, just do the thing. I don’t care what you call yourself — if you quack, you’re in.”

That’s duck typing in a nutshell. But let’s unpack this polite chaos.

🧩 Abstract Classes and Interfaces: The Formal Way

In statically typed worlds, interfaces and abstract classes define explicit contracts.

You must implement specific methods before you can create an object of that type.

In Python, you can achieve something similar using the abc (Abstract Base Class) module.

Here’s how that looks:

This approach is explicit — you’re telling Python exactly what a “Quackable” must do, and it enforces it before runtime.

🦆 Duck Typing: The Chill, Flexible Cousin

Now compare that with our earlier example:

class Person:

def quack(self):

print(“I’m pretending to be a duck!”)

def make_it_quack(thing):

thing.quack()

No inheritance, no contracts, no paperwork.

Just two entities who happen to have the same behavior.

That’s the beauty of duck typing — Python only cares what an object can do, not what it claims to be.

⚖️ When to Use What

| Use Case | Recommended Approach |

|---|---|

| Small, flexible scripts or prototypes | Duck typing — fast, readable, minimal boilerplate |

| Large-scale systems or public APIs | Abstract classes or Protocol — explicit contracts improve maintainability |

| Type-safe flexibility | Use typing.Protocol for static validation + duck typing behavior |

So, if you’re building a one-off data pipeline, duck typing will feel gloriously free.

But if you’re writing the next Django or Flask — something others will extend — a little discipline (via ABCs or Protocol) will save future headaches.

🧠 The Pythonic Balance

Python’s philosophy isn’t “never use types.”

It’s “use them when they make sense.”

Duck typing shines for quick iteration, dynamic behavior, and elegant simplicity.

Abstract classes shine for structure, reliability, and clear contracts.

In short:

“Duck typing lets you improvise. Abstract classes make you rehearse.”

Both have their stage — use the right one for your performance. 🎭

VIII. Advantages and Disadvantages of Duck Typing

✅ Advantages of Duck Typing

-

Flexibility

Duck typing allows your functions to work with any object that implements the expected behavior. No inheritance or formal interfaces required. Your code can quack with aDuck, aPerson, or even aRobotDuck. -

Simplicity and Readability

Without boilerplate type declarations, Python code reads almost like natural language. For example:

It’s short, clear, and immediately understandable — the Pythonic dream.

-

Rapid Prototyping

Want to test a new idea? Duck typing lets you focus on behavior first, structure later. You can swap objects freely during development without refactoring your entire codebase. -

Code Reusability

Functions and APIs written with duck typing work across multiple object types as long as they implement the required methods. This reduces duplication and encourages modular design.

❌ Disadvantages of Duck Typing

-

Late Error Detection

Errors appear at runtime rather than compile-time. Forgetting a method or attribute can result in anAttributeErrorwhen your program is already running.

-

Harder Debugging

Because types aren’t explicit, tracing where an error came from can be tricky — especially in large codebases. -

Less Explicit Contracts

Unlike abstract classes or interfaces, duck typing doesn’t enforce method presence upfront. Developers need to rely on documentation or type hints to know what’s expected. -

Potential Performance Concerns

While generally negligible, excessive runtime checks or conditional duck typing logic may slightly impact performance in critical loops.

⚖️ Trade-offs: When to Embrace vs Avoid

-

Embrace duck typing when:

-

You’re prototyping or scripting.

-

You need flexible, reusable code.

-

You’re working in a Pythonic ecosystem where behavior matters more than type.

-

-

Avoid duck typing (or combine with type hints/ABCs) when:

-

You’re building large, team-based systems requiring explicit contracts.

-

Runtime errors could cause critical issues.

-

You want static analysis to catch mistakes early.

-

🦆 Quick Real-Life Example

Consider a function that makes things quack:

This EAFP (“Easier to Ask Forgiveness than Permission”) style handles missing methods gracefully — a Pythonic way to mitigate duck typing’s downsides.

🧠 Bottom Line

Duck typing is a double-edged sword:

-

Powerful, flexible, and Pythonic when used wisely.

-

Potentially error-prone if you ignore testing, documentation, or type hints.

The trick is balance: embrace freedom, but equip yourself with tools and best practices to keep your ducks in a row.

IX. Best Practices for Using Duck Typing in Real Projects

🧰 Tip 1: Prefer EAFP Over LBYL

In Python, there are two main approaches to handling potential attribute/method issues:

-

LBYL (“Look Before You Leap”) — manually check if the object has the required method or attribute:

-

EAFP (“Easier to Ask Forgiveness than Permission”) — try the action and handle exceptions if it fails:

Pythonic wisdom: prefer EAFP. It’s concise, readable, and embraces Python’s dynamic nature.

🦆 Tip 2: Use Type Hints for Clarity

Even in dynamic code, type hints add clarity without rigidity.

-

typing.Protocollets you declare expected behavior (duck typing style). -

Tools like mypy or Pyright catch errors before runtime.

Example:

This balances flexibility with predictability — your code can handle new duck-like objects, but developers (and tools) know what’s expected.

🧩 Tip 3: Validate Objects When Needed

In large projects, runtime errors can be costly.

-

Use

hasattr()orcallable()checks sparingly, mostly for external input or untrusted objects. -

Consider unit tests that verify objects implement required methods.

This ensures you catch missing methods early without compromising flexibility.

🐍 Tip 4: Maintain Clear Documentation

Document expected behavior in your function docstrings.

For example:

Parameters:

thing: Any object with a quack() method.

“””

thing.quack()

Good documentation prevents misuse and improves maintainability, especially in team projects.

⚡ Tip 5: Test Thoroughly

Dynamic behavior means runtime errors can slip through.

-

Use unit tests to ensure objects behave as expected.

-

Test multiple “duck-like” implementations, especially custom or third-party objects.

🦆 Tip 6: Combine Duck Typing with Type Hints in Production

In production code, combining duck typing with type hints and static analysis gives you:

-

Flexibility to work with any compatible object.

-

Safety from catching errors early.

-

Readability for future maintainers.

🧠 Bottom Line

Duck typing is incredibly powerful — but like any tool, it works best when paired with best practices:

-

Prefer EAFP over LBYL.

-

Use type hints and

Protocolfor clarity. -

Validate objects responsibly.

-

Document expectations clearly.

-

Test thoroughly.

Follow these tips, and your Python code will remain flexible, Pythonic, and maintainable, even as your codebase grows.

X. Real-World Applications of Duck Typing

🏗 Python Frameworks That Rely on Duck Typing

Duck typing isn’t just a cute concept — it’s everywhere in Python’s ecosystem. Many frameworks and libraries are built around the idea that behavior matters more than type.

1️⃣ Django ORM Models

Django’s ORM lets you interact with database tables using model classes. You don’t need to inherit from a strict interface — as long as your class implements the expected methods (save(), delete(), objects.filter(), etc.), Django happily treats it as a model.

Duck typing ensures flexibility while letting Django perform its magic behind the scenes.

2️⃣ Pandas DataFrames

Pandas heavily relies on duck typing for array-like operations.

DataFrames mimic NumPy arrays’ behavior. Functions that operate on “array-like” objects don’t care if it’s a NumPy array, a Series, or a DataFrame — as long as the object implements the necessary operations.

3️⃣ Flask Request/Response Objects

Flask treats request and response objects like any object that implements expected behavior.

Flask doesn’t demand a specific type for the return value — strings, dicts, or Response objects work as long as they behave correctly. This flexibility is a direct benefit of duck typing.

4️⃣ File Objects and Stream APIs

As we saw earlier, file-like objects (StringIO, sockets, open files) all share methods like .read() and .write(). Functions that accept “file-like objects” don’t care about the actual class, only the behavior.

import io

fake_file = io.StringIO(“Duck typing is awesome!”)

print(read_file(fake_file))

This allows developers to swap different backends (disk, memory, network) seamlessly.

⚡ Why Duck Typing Matters in Real Projects

-

Flexibility – Swap objects without changing code.

-

Extensibility – Add new types easily.

-

Code Reusability – Functions work with any compatible object.

-

Framework Design – Many Python libraries rely on duck typing to offer clean, generic APIs.

Duck typing isn’t a quirky concept — it’s a foundational principle of Pythonic design. It makes Python libraries elegant, intuitive, and flexible.

🦆 Quick Takeaway

If it quacks like the object your framework expects, Python will let it quack. No boilerplate, no rigid contracts, just behavior-first design.

XI. Common Misconceptions About Duck Typing

❌ Myth 1: Duck Typing Means “No Typing”

Some developers hear “duck typing” and imagine Python is completely type-free chaos.

Reality? Duck typing is about behavior, not the absence of structure.

-

Python still has types (

int,str,list, etc.). -

Type hints (

typing.Protocol) let you enforce expected behavior. -

IDEs and static analysis tools can still warn you about misuse.

Truth: Duck typing is flexible typing, not no typing.

❌ Myth 2: Duck Typing Is Unsafe or Unprofessional

Critics argue that duck typing leads to runtime errors and messy code.

Sure, if you ignore testing, documentation, or type hints, mistakes happen. But in real-world projects, duck typing:

-

Powers mature frameworks like Django, Flask, and Pandas.

-

Allows polymorphic APIs without rigid inheritance.

-

Works beautifully with type hints for safety and readability.

Truth: Duck typing is safe and professional when combined with best practices.

❌ Myth 3: Duck Typing Can’t Be Used in Large Projects

Some think duck typing is only suitable for small scripts or prototypes.

In reality:

-

Large projects like Django, Flask, and Pandas rely heavily on duck typing.

-

Proper use of type hints, EAFP, and protocols scales duck typing for big systems.

-

It encourages modular, reusable, and testable code, which is ideal for large teams.

Truth: Duck typing scales — just follow Pythonic best practices.

🦆 Key Takeaway

Duck typing is not a shortcut for laziness. It’s a design philosophy:

“Focus on what an object can do, not what it is.”

When used responsibly, it allows for flexible, maintainable, and Pythonic code — no matter the project size.

XII. Conclusion

🦆 Quacking to a Close

“If it looks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck…” — by now, you know the Python twist: if it behaves like the object you expect, Python will let it pass.

Duck typing is more than just a clever metaphor. It’s a core principle of Python’s design philosophy that emphasizes:

-

Behavior over type

-

Flexibility over rigidity

-

Readability and simplicity

From rapid prototyping to robust frameworks, duck typing powers Python code that’s intuitive, reusable, and extensible.

🔧 Balancing Freedom with Safety

Yes, duck typing comes with risks — runtime errors if objects don’t implement expected methods, and occasional debugging headaches. But Python gives you tools to mitigate those risks:

-

Type hints and

Protocolfor static analysis -

EAFP (Easier to Ask Forgiveness than Permission) for graceful error handling

-

Testing and clear documentation to keep things maintainable

Combine these practices, and you get Pythonic flexibility without chaos.

🌍 Why It Matters

Duck typing isn’t just an academic concept; it’s foundational to the Python ecosystem:

-

Django and Flask rely on it for models and request/response handling.

-

Pandas leverages it to behave like NumPy arrays.

-

File-like objects, iterables, and APIs all thrive on behavior-first design.

Mastering duck typing gives you the confidence to write clean, flexible, and elegant Python code that works with any object that “quacks.”

📚 Call to Action

Want to go deeper? Check out:

-

PEP 484 — Python type hints

-

PEP 544 — Protocols for structural subtyping

-

Official Python documentation on dynamic typing and abstract base classes

With practice, duck typing becomes second nature — and you’ll find yourself thinking less about types and more about what your code can do.

🦆 Final Quack

Duck typing is Python’s way of embracing freedom, simplicity, and readability.

It’s quirky, flexible, and deeply Pythonic — but when paired with type hints, tests, and clear documentation, it’s also powerful, professional, and scalable.

So go ahead: let your ducks quack, your functions fly, and your Python code shine.